Taking the 'next step' of innovation: Five pillars for senior leaders to lead civic culture change

Article highlights

How can civic innovators reflect on their strengths and chart a path forward for their cities? The 5 innovation development pillars are a powerful tool for public servants seeking to do just that.

Share articleInnovation is a question of culture change, of instituting a new modus operandi for government characterized more by “what if?” than by “but what if not?”

Share articleExplore the 5 innovation development pillars, which aims to support city leaders 🌇 by posing questions along the dimensions of personal, project, personnel, ecosystem, and community development.

Share articlePartnering for Learning

We put our vision for government into practice through learning partner projects that align with our values and help reimagine government so that it works for everyone.

Here at CPI, we believe the emerging practice of civic innovation offers one of the most powerful opportunities for us to deliver against our vision for equitable, collaborative, and bold government. A term that defies neat definition, innovation represents a package of skills and mindsets that can help city officials center community voices (equity), partner across silos (collaboration), and embrace experimentation and learning (boldness).

Through our support on Innovation Training and the innovation track of the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative, CPI has guided 80 cities worldwide to develop fundamental innovation skills and apply them to pressing problems facing their communities. We have watched in awe and excitement as city officials “catch the innovation bug” while adopting practices like community research and co-design, cross-departmental stakeholder engagement, and iterative prototyping. By using these skills, innovation proposes a new approach to public service that can help governments combat cultures of hierarchy, fear of failure, and tradition. Innovation is a question of culture change, of instituting a new modus operandi for government characterized more by “what if?” than by “but what if not?”.

But culture change is hard, and even harder if early adopters don’t have allies to help champion their efforts. This is a central challenge of embracing civic innovation: it often “bubbles up” in pockets across city hall but requires a collective commitment to unlock its full potential. Innovation can save cities big money by helping government teams identify early which solutions are worth pursuing, but departments must reconsider timelines, budgets, and success metrics to do so. An innovation-minded team can only get so far by conducting community research if larger project structures don’t allow space for further iteration and learning.

Here, senior leaders have an unparalleled opportunity to lead on this new form of public service. Based on our work with 80 cities, we see that innovation thrives most when staffers at all levels of government work in tandem: frontline staff lead the tactical work of researching, ideating, and prototyping “from the bottom up,” while senior leaders tackle the structural barriers to culture change “from the top down.”

Innovation is a question of culture change, of instituting a new modus operandi for government characterized more by “what if?” than by “but what if not?”.

In late 2022, CPI began exploring new ways to support frontline staff and senior leaders in their bi-directional efforts to scale innovation. In partnership with the Bloomberg Center for Public Innovation at Johns Hopkins, we piloted the Activating Innovation Champions program (AIC). The program challenged seven cities to launch two new projects using the innovation approach they learned in Innovation Training or the Innovation track of the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative.

In true “bottom up, top down” fashion, we supported frontline staff to replicate their skills on new teams while our coaches worked with senior leaders to deepen their understanding and commitment to innovation. The AIC pilot also included structured “touchpoints” between frontline staff and their leaders, which served as opportunities for strategic alignment, storytelling, and celebration. After just six weeks, our seven cities collectively launched 14 new innovation projects and introduced 55 new staff and leaders to innovation methodologies. On the leadership front, over 30 mayors, senior leaders, and department heads participated in our Master Class workshops about scaling innovation, and four worked one-on-one with our expert coaches to develop specific commitments to advance innovation as part of the AIC program.

Five Innovation Development Pillars

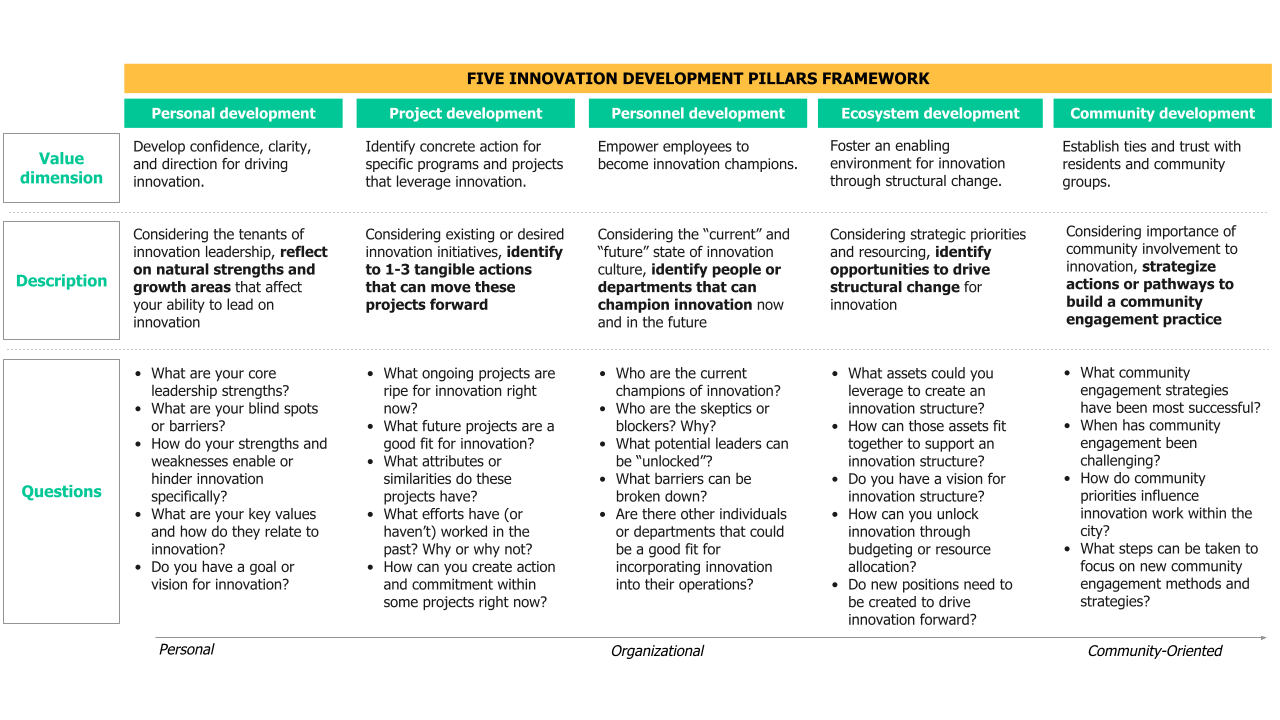

No matter where cities were in their innovation journey, we found many leaders pondering a similar question: “I’ve seen the value in this approach, now how can I best contribute moving forward?” In the AIC program, our answer to this challenge was what we call the “Five Innovation Development Pillars” framework. Recognizing the need for guidance on that next step, the framework aims to support leaders by posing questions along five innovation dimensions. We designed the Pillars to help leaders reflect on discrete, immediate ways to capitalize on the “bottom up” innovation work in their cities—one of the more powerful moves to inspire confidence and momentum in pioneering teams.

The five Pillars fall on a spectrum, along the dimensions of Personal to Organizational and Community-Oriented. While each pillar can stand on its own, there is value in the spectrum itself. First, it helps leaders to distinguish the scope of influence of each decision, with the pillars on the left being more discrete or reflective and the ones on the right being more structural or strategic. This is a valuable gradient to help leaders chart where they can have the most impact based on their unique leadership position or the state of innovation in their city. Second, the dimensions highlight our belief that innovation’s value is not just its approach to structuring projects and teams (Organizational), but also in its power to transform our mindsets around public service (Personal) and the relationship between government and citizens (Community-Oriented) overall. Below, we offer a brief description of each pillar and how they deliver against these three transformative dimensions.

Personal Development: An excellent first step in innovation leadership is reflecting on where your existing skill set maps to the new task at hand. As a starting point, this pillar is less about stretching you out of your comfort zone (addressing your opportunity areas) than about helping you acknowledge how you already embody innovation mindsets, even without knowing! We believe this strengths-based approach is the best way to start seeing yourself as a natural innovator. Over time, you can tackle blind spots and opportunity areas alongside partners as part of your collective learning journey. The guiding question here is:

In what ways am I naturally innovative, and how can I lead more explicitly on innovation with this in mind? Down the line, where could I develop my mindset further to deliver better on the innovation mission?

Project Development: As decision-makers, senior leaders are always assessing the pool of potential solutions and pursuing those which promise the best outcomes within given constraints. Every so often, however, challenges arise where the solution is seriously unclear or could benefit from new insight. This is where innovation comes in: it helps cities imagine new solutions, test them iteratively, and prioritize for impact. Whether it’s launching a new innovation project or simply infusing an existing one with a few innovation methodologies, leaders are well-positioned to unlock high-level project opportunities that help teams reach this new level of clarity. In our AIC program, leaders asked themselves:

Which problems require a breadth of new perspectives to improve outcomes, and what are some ways (big or small) I can unlock opportunities for teams to explore and iterate?

Personnel Development: Innovation is naturally cross-departmental. It unearths solutions that often require collaboration across functional or thematic silos, so it’s important to have allies wherever you go in city hall. As a first step, "getting the right stakeholders in the project room” is an excellent cross-departmental approach. In the long term, however, collaboration will likely require identifying (and developing!) staffers with a strong potential for innovation leadership. Often these folks are early adopters that are already looking for more cutting-edge professional development opportunities. You may ask yourself:

Who are my future champions, my quick allies, and my biggest skeptics? How can I unlock each of their potentials?

Ecosystem Development: As your city advances in its innovation journey, your focus will likely expand from unlocking specific projects or people to establishing an organization-wide strategy. At first, this may mean embedding innovation into budgets or resourcing conversations, i.e. leveraging the available assets for structural change. Over time, we find cities start to ask how to build an innovation structure, or a specific home for innovation within their city. In our own AIC program, Amarillo is building an Office of Engagement & Innovation that functions as an in-house consultancy, and Dublin is embedding innovation skills into departments’ employee toolkits. There is no one-size-fits-all solution for cities, so we encourage you to ask:

What assets can I leverage to drive structural change? Which infrastructure would most benefit my city, and what budgets or other resources can we allocate to allow it to thrive?

Community Development: Civic innovation projects usually begin with a “bottom up” research phase with the residents most affected by the problem. Interviews, in-context observations, surveying, and rapid prototyping are all part of the civic innovator’s community engagement toolkit. As your community-oriented work grows, so too will your desire to create a stronger, more institutionalized dialogue between your departments and residents. For a leader, building networks of community members and groups is the ultimate stakeholder engagement opportunity; it encourages cities to approach residents like “formal” partners and begin practicing shared power and decision-making principles. As you think about how to create networks and pathways between government and residents, ask:

Where are community groups already leading on community advocacy? What engagement models can I institute to ensure community members continually shape our work?

Through our innovation work with 80 cities, it’s clear that the task of sparking an interest in innovation is distinct from the work of sustaining it over time. Innovation promises to transform a city’s approach to public service and improve outcomes while minimizing risk and costs. But the path to creating an institutionalized culture of innovation can feel uncharted and requires flexibility and buy-in across city hall. Our hope is that the Five Innovation Pillars helps civic innovators reflect on their strengths and resources and chart a path forward for their city based on the opportunities they identify. And while the pillars are aimed at senior leadership with the influence to enact high-level change, we’ve also seen middle managers and early-career professionals find value in the reflection questions—both as a framework for their own leadership and for guiding their engagement with leaders above them. As we advance our work with innovation scaling teams and senior leaders, stay tuned for more insights on innovation leadership and culture change in city hall!

Written by:

You may also be interested in...

Civic innovation project deep dive