Listening to the Past to Design the Future

Article highlights

'For systems-led design to be its best, our focus needs to be the past as much as it is the future.' - @LukeCraven from @ato_gov_au

Share article.@LukeCraven encourages #systemsledthinking to consider the importance of the past, through learnings from the field of #medicine

Share article.@LukeCraven uses the #futurescone to portray the absence of the past when designing projects about the future. But, this can change.

Share articlePartnering for Learning

We put our vision for government into practice through learning partner projects that align with our values and help reimagine government so that it works for everyone.

Go to the doctor and they won't begin to treat you without taking your history - and not just yours, but that of your parents and grandparents before you. The rationale is simple: you need to understand a patient's history to fully understand the causes of their ailment and to develop effective treatments.

It is easy to belabour the doctor-patient metaphor, but the much of the work of redesigning systems is in correctly diagnosing ailments and proposing treatments to deliver “system health”.

But so much of our work exhibits a distinct lack of historical emphasis. Design projects commonly involve deep exploration of a system's current and future states, but we spend significantly less time understanding previous change, its drivers, and the trajectories that have emerged over time.

You might ask why the past matters when we are focused on changing the system. We like to think of complex systems as characterised by consistent change, but they also tend to shift and oscillate within a given steady state, following regular patterns of change, stability, and return. Think of a person who attempts to change but reverts to characteristic (albeit slightly different) behaviour. Habits and behaviours are, once crystallised, hard to break.

These steady states (“attractors”) may not be immediately visible, and may not be single points, but patterns of points. Relatively simple attractor patterns have been found in share prices in the financial market, in biological systems such as beat to beat variations in heart rate, and in human behaviour.

To a certain extent, we need to know what change has been possible in the past to know what kinds of change are possible in the future.

The History of History-Taking in Medicine

The practice of history-taking in medicine emerged at the end of the eighteenth century alongside the advent of hospital medicine and the standardisation of the of the clinical process. In various guises, it has been important ever since.

The widely-used medical textbook Clinical Investigation, written by E. H. Stokes in 1953, noted that: “Without any doubt the history is the most important single factor in arriving at a diagnosis … errors most frequently arise in internal medicine because the clinician does not know what questions should be asked. The art of history taking requires knowledge of the disease and long experience of sick people and can be acquired only through hard work.”

There is a lot to like about this quote: the importance placed on history for diagnosing problems in the present; the description of history-taking as art, not science; and the focus on learning to ask the right questions.

Taken together, these elements are prescription for the limitations in our current practice. For systems-led design to be its best, our focus needs to be the past as much as it is the future.

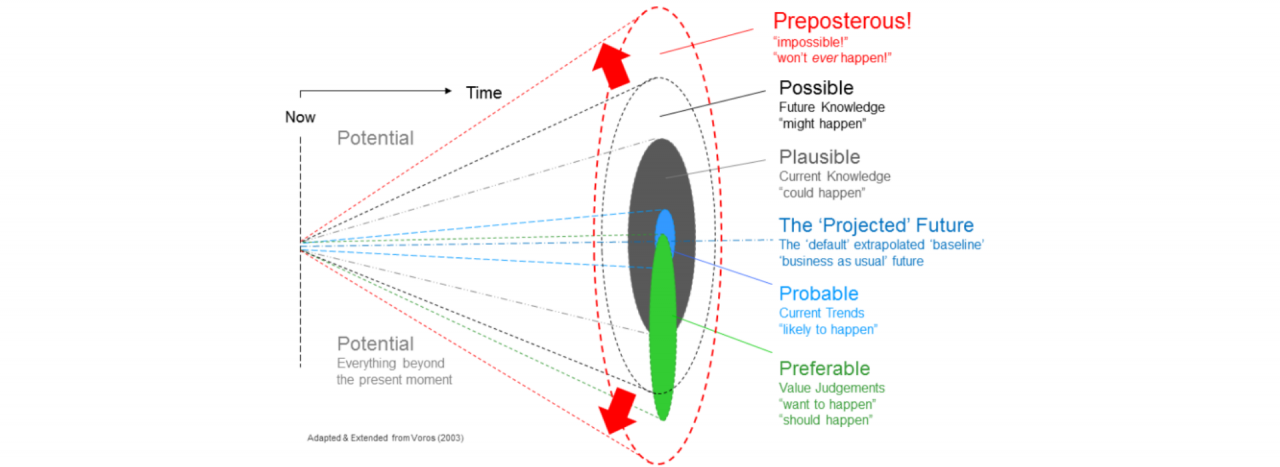

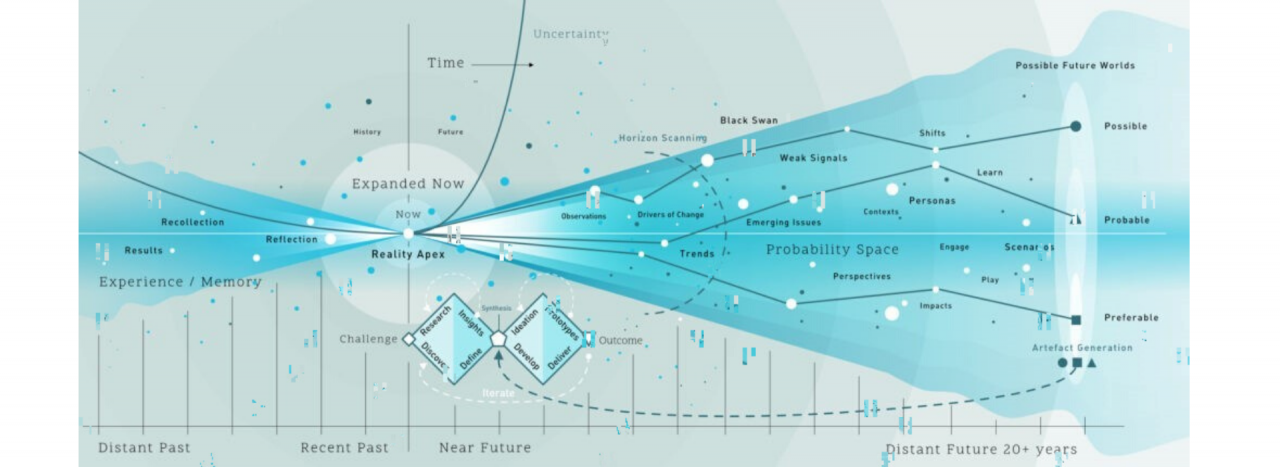

This likely requires a significant shift in the tools that designers use to make sense of the world and explore future possibilities. Take one example, the futures cone, which is a method common to work in foresight and speculative design.

The method is used to portray four classes of alternative future (possible, plausible, probable, preferable) situated against the structures of the present.

Notably absent in the model is the past, the implication being that all we need to project our designs and their impact into the future is an understanding of the current state.

But this doesn't have to be the case. Newer iterations of the futures cone have begun to explicitly include history, experience and memory and their role in helping designers shape future systems.

Learning from Medicine: Back to the Future

Most of us know Hippocrates for his oath, but we owe him for much more. His work is widely credited with setting the foundations of modern clinical medicine. He wrote one of the earliest works of medicine, Book of Prognostics, which is believed to have been written around 400 BC.

The book opens with the following statement: "It appears to me a most excellent thing for the physician to cultivate Prognosis; for by foreseeing and foretelling, in the presence of the sick, the present, the past, and the future, and explaining the omissions which patients have been guilty of, he will be the more readily believed to be acquainted with the circumstances of the sick; so that men will have confidence to intrust themselves to such a physician. [emphasis mine]"

It seems we can learn much about the present state of medicine from a study of its roots. The lesson is a powerful one: designing change requires deep work to understand the system, its present, past, and future. Listening to the past can make visible healthy horizons.

The Future of Government

We’ve been speaking to the citizens, governments, public servants, and other changemakers who are reimagining government and making this new future a reality.

Written by:

You may also be interested in...

Climate leaders overcome funding challenges by “hacking” bureaucracy and building resilient coalitions

How do you understand impact in complex systems?

PRESS RELEASE: Centre for Public Impact announces Natalie Creary as Regional Director for Europe

Embracing the paradox: the urgency of climate action and the power of learning from failure