The Opportunity Project for Cities: Lessons from Saint Paul and San José

About this report

This report was compiled following the first iteration of the TOPcities program, an 18-week innovation sprint through which two local governments worked with community and tech partners to develop tools that would address pressing local challenges emerging from COVID-19. The Centre for Public Impact (CPI) is a non-profit organization founded by Boston Consulting Group with the mission to reimagine government to work better for everyone. The Beeck Center for Social Impact + Innovation at Georgetown University reimagines systems for public impact using design, data, and technology. Beeck Center projects test new ways for public and private institutions to leverage data and analytics, digital technologies, and service design to help more people.

CPI and the Beeck Center partnered to launch the TOPcities program, and have developed this joint report to document findings and lessons to inform wider efforts in the field of civic innovation. The TOPcities program was developed with generous support and guidance from the Knight Foundation and Google.org. This report was written by Katie Stenclik, Andrea Mirviss, Rebecca Ierardo, and Katya Abazajian. It was released on August 19, 2021, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license and should be cited as: “The Opportunity Project for Cities: Lessons from Saint Paul and San José” (2021). Washington, D.C.

Contributing organizations:

The Centre for Public Impact is a not-for-profit founded by Boston Consulting Group. Believing that governments can and want to do better for people, we work side-by-side with governments—and all those who help them—to reimagine government, and turn ideas into action, to bring about better outcomes for everyone. We champion public servants and other changemakers who are leading this charge and develop the tools and resources they need so we can build the future of government together.

The Beeck Center for Social Impact + Innovation at Georgetown University reimagines systems for public impact using design, data, and technology. Beeck Center projects test new ways for public and private institutions to leverage data and analytics, digital technologies, and service design to help more people.

The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation is a national foundation with strong local roots. We invest in journalism, in the arts and in the success of cities where brothers John S. and James L. Knight once published newspapers. Our goal is to foster informed and engaged communities, which we believe are essential for a healthy democracy.

Google.org, Google’s philanthropy, supports nonprofits that address humanitarian issues and apply scalable, data-driven innovation to solving the world’s biggest challenges. We accelerate their progress by connecting them with a unique blend of support that includes funding, products, and technical expertise from Google volunteers. We engage with these believers-turned-doers who make a significant impact on the communities they represent, and whose work has the potential to produce meaningful change. We want a world that works for everyone—and we believe technology and innovation can move the needle.

Introduction

There is a common paradox in local government: troves of public data, increasingly complex challenges, and mismatched capacities to use the former to address the latter. But public servants working in local government know that it is a tall order to find effective and impactful uses for public data when targeting their communities’ most pressing challenges. Adding to this challenge is the fact that local civic innovation is often contained to the work of innovation teams or other technical departments that have the skills required to run design sprints and manage products that make up cities’ technical or data infrastructure. This can limit broader access to key innovation skills and approaches that are necessary for helping public servants creatively respond to the multi-faceted challenges of today.

The need and potential to address governments’ innovation and digital capacity has never been greater. Due to COVID-19, communities across the country are struggling with job, housing, and food security, alongside other challenges that hinge on equitable access to digital services. In the past year and a half of responding to a global pandemic, local governments have had to take on greater responsibilities with fewer resources.

It’s time for local governments to get creative. Local governments have been innovating quickly and demonstrating their ability to shift internal culture and policies to match residents’ needs for more responsive, equitable, and data-informed governing. But they have room to grow, and they cannot do so alone. In order to nimbly respond to the “new normal,” governments need to partner with community members who best understand local challenges and technologists who can help them deliver on their missions.

This is why we developed the TOPcities model. Designed after the federal initiative, The Opportunity Project, TOPcities is a program dedicated to developing local government’s capacity to partner with communities in order to address local problems using digital innovation. While the inaugural TOPcities cohort focused on COVID-19 related challenges in two cities, Saint Paul, MN, and San José, CA, our hope is that local governments in rural communities, towns, and cities of all sizes will adopt the TOPcities model to leverage the power of their communities.

Our story: designing TOPcities

In 2020, the Centre for Public Impact (CPI) and the Beeck Center for Social Impact + Innovation at Georgetown University partnered to launch a pilot program, The Opportunity Project for Cities (TOPcities). We designed TOPcities to help local governments develop the skills to become more adaptive, collaborative, and creative as they navigate challenges resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. In doing so, we sought to help them leverage these newfound capacities to address local problems using technology and turn important, underutilized government data into tools for public good.

The overall structure and approach of TOPcities was inspired by the U.S. Census Bureau’s The Opportunity Project (TOP), which brings together cross-sectoral organizations to leverage federal data to create new technologies. Launched in March 2016 as a White House initiative, TOP has culminated in more than 100 products that translate federal data to useful public tools. TOPcities would not have been possible without the excellent foundation the federal team developed, and we can’t thank them enough for their gracious support and guidance throughout this process.

In transitioning the federal TOP model to the local level, our goals were to:

Help governments partner with community organizations to develop accessible and innovative minimum viable products (MVPs) that respond to COVID-related challenges.

Develop the capacity of public servants to:

Adopt new strategies for innovation that are oriented around listening, learning, and collaborating with community stakeholders.

Strengthen capacity to design equitable digital services and apply open data.

Build pathways for technologists and communities to participate in local civic innovation projects, including by documenting effective strategies for cross-sector collaboration.

Create a learning network to share best practices across sprint teams and with other local governments more broadly.

In order to achieve these goals, sprint teams used best practices from human-centered design (HCD) and open data. HCD is a method for solving problems that is rooted in learning from people’s daily experiences. HCD is a core feature of the TOP model because it provides tools for public servants to understand resident experiences and center them when making decisions.

Another core feature of the TOP model is open data. Public servants need support to apply underutilized public data that could be used to solve public challenges if the data is shared in ways that inform residents or help them to find the services they need. City governments leverage available public data - primarily open data or information that is shared freely and maintained for public use - to develop innovative technical solutions that meet residents’ needs.

When we adapted TOPcities to meet the local context, we supplemented the original TOP model with intensive coaching and training to help our local government partners deepen their collaborations with technologists and local community organizations. Hands-on support was essential to ensure that local government staff participating in the sprint had the capacity to manage sprints in addition to their myriad responsibilities as frontline staff responding to the effects of COVID-19. By operating TOPcities, we sought to improve each government’s understanding of its own available data, create opportunities to strengthen data quality, and democratize access to government information.

The TOPcities model helps public servants adopt new ways of analyzing and addressing systemic challenges, collaborating across sectors, engaging with residents, and leveraging public data to develop impactful solutions. Our inaugural TOPcities sprint provides several lessons on the value of helping governments develop new approaches that center communities as they respond to modern challenges.

The first sprint

The first TOPcities sprint launched in February 2021 with two U.S. cities: San José, CA, and Saint Paul, MN. Each city formed cross-sector teams that included municipal employees, technologists from Google.org, and local community partners - Catholic Charities of Santa Clara County in San José and M Health Fairview in Saint Paul. Over the course of four months, the teams engaged in a product design sprint comprised of three main parts: understanding the problem by engaging with community members and other key stakeholders; developing a product to address the problem; and launching a product for public use. Our TOPcities toolkit provides a more detailed description of how this program works in practice so that local governments can replicate TOPcities sprints on their own.

For this inaugural sprint, both teams focused on addressing housing challenges that were exacerbated by COVID-19. In San José, the sprint team focused on strategies to prevent residents from being evicted due to inability to pay rent. In Saint Paul, the sprint team sought to improve access to services for residents experiencing homelessness. The sprint teams engaged with more than 100 residents, service providers, and public servants across the two cities to learn more about their respective challenges and get feedback on the products they designed to address them. By the end of their sprints, both San José and Saint Paul developed prototypes that are designed based on resident needs and that leverage data and technology to address local challenges. The rest of this section describes how each city addressed its problem through the sprint and lessons learned.

Case study one: preventing evictions in San José, California

The problem

In the wake of COVID-19, thousands of San José residents have relied on government eviction moratoria to avoid eviction due to inability to pay rent. Despite this temporary relief, the end of the moratoria will require residents to provide months of back rent to their landlords, or else face losing their homes. According to a July 2020 study from Working Partnerships USA and the Law Foundation of Silicon Valley, this challenge is particularly acute for “people of color, women-headed households, and families with young children” in San José. In order to mitigate the risk of mass evictions, city, county, state, and federal aid is available to renters and landlords to make up for months of lost payments. As such, the San José sprint team looked to public data and the community to seek answers to two central questions: how much aid would need to be distributed to residents, and how could the City ensure that San José residents receive the assistance they need?

The team

The San José sprint team consisted of representatives from the City of San José’s Rent Stabilization Program, Catholic Charities of Santa Clara County (Catholic Charities), and Google.org. The team was also coached by expert civic technology advisor, Alicia Rouault, co-director of State and Local Practice at 18F.

City staff from the Rent Stabilization Program contributed topic-based expertise and helped the team navigate San José’s complex political ecosystem. As the community partner, Catholic Charities represented the community perspective throughout the sprint and helped the sprint team get feedback from service providers and residents during user research and product development. The City partnered with Catholic Charities for the sprint due to their deep community relationships and expertise in collaborating with the City to provide direct support, such as food and rental assistance, to residents experiencing financial hardship. CPI and the Beeck Center helped the sprint team connect with Alicia Rouault as a product advisor because of her expertise in civic technology and experience working on state and local tech initiatives at a national level. Additionally, Google.org contributed product managers, engineers, data scientists, and user experience designers to support with community research, product brainstorming, technical assistance, and product development.

The sprint

Problem understanding

At the start of the sprint, the San José sprint team followed the City’s guidance that the best way to help residents relying on the eviction moratoria would be to better measure the “eviction cliff.” The “eviction cliff” is defined as the number of households that are at risk of eviction due to inability to pay rent once the moratoria are lifted. This guidance was rooted in the assumption that calculating this “eviction cliff” would help the City to better allocate resources and target funding to those who needed it most.

To better understand this problem, the sprint team took a two-pronged approach. First, the sprint team set out to find public data that could help them to identify which residents would be most at risk of eviction when the moratoria ended, and then estimate the magnitude of back-rent owed by these residents. The City began compiling data from eviction notices submitted by landlords but soon realized this information was either out of date or incomplete. Landlords had fallen behind on filing eviction notices with the City because they were unable to evict tenants during the moratoria. Second, the sprint team interviewed City officials, community leaders, landlords, and tenant organizers to learn from their experiences with this challenge. In partnership with Catholic Charities, they also surveyed 38 residents experiencing economic distress at local food banks over three days.

The insights from this research process ultimately shifted the sprint team’s project focus. The team discovered that even if they identified the individuals most in need of aid, they would struggle to get this aid into those residents’ hands. Further, there were serious barriers preventing residents from accessing rental aid that could help them avoid eviction in the first place. A deeper analysis of this key realization and three important insights about San José’s rental assistance landscape follows:

The rental assistance process is arduous, confusing, and emotionally taxing. Many don’t know how to get help or cannot access it due to technology constraints. Even for those who have access to technology and the skillsets to use it, the existing rental assistance process is deeply complex. The resident application alone is 37 pages long, and there are often linguistic barriers for San José’s non-English speaking residents, as the technical nature of the application can be difficult to translate clearly. The sprint team also learned that even if tenants or landlords completed this arduous application, they have no way to track their application’s status, which can be discouraging and stressful. One landlord shared, “It's a complicated process. It requires tenants to respond and provide documentation. If they don't respond and provide documentation, they don't know if they get their money back.” Many give up in the face of the sheer magnitude and complexity of paperwork they must provide to get assistance.

Many residents who need aid cannot access this complicated system even if they want to: according to a city council member, 20 percent of residents who would apply for relief don't have reliable internet access. These populations rely on phone or in-person resources when seeking services, or use the web through a proxy - such as Catholic Charities or a public library - many of which have been inaccessible due to pandemic restrictions. In addition to digital access barriers, the sprint team also discovered a major information gap. In some cases, residents did not even know that rental assistance was available or that they were eligible.

Guadalupe Gonzalez Rent Stabilization Program Analyst, City of San José"The research phase of TOPcities really honed in on the fact that people need information, that there’s a lack of information, and we need to understand what information we can get out right now."

Many tenants and landlords do not trust the government to provide assistance. Widespread mistrust of government meant that most residents were either unaware of or disinclined to seek out municipal resources. One service provider shared in their interview that many residents “don’t trust government sites, the government in general, or anything that asks them to upload personal information online.” By contrast, a city council member shared that community organizations were already accepted as a trusted voice of truth, that “the best way to reach [the most vulnerable] is through community partners like Catholic Charities or Sacred Heart. They are more likely to trust those who have a physical presence in their communities and those who can speak their language.”

Facing increasing demand and a complex system, community organizations struggle to meet needs. Interviews with community organizations pointed to staff shortages and limited technical capacities, which diminished their ability to administer rental assistance in a time-efficient way. One service provider shared, “When the City launched DIRA [an aid program set up by Governor Newsom to give $500 to undocumented immigrants, we were], getting 4,000 calls a day for help. It crashed our system and we couldn’t even take all the calls and had to replace our system.” Due to increased need and COVID-19 precautions, most service providers, including Catholic Charities, are requiring residents to make appointments to get help with their rental assistance application and no longer offer walk-ins, which can also be a barrier to accessing assistance. Staff from Catholic Charities estimated that each application takes roughly 2 to 4 hours and about 2 to 3 separate appointments to complete. Catholic Charities and other service providers spent a lot of this time helping residents understand their eligibility, find documentation they need for their application, and assess which ID requirements residents could meet to file the application.

Based on the needs exposed by the community research process, the sprint team shifted their problem focus from measuring the eviction cliff to making the process of applying for rental assistance more transparent and accessible. They also shifted their data collection away from the magnitude of back rent owed by residents, because, as one City staff member shared, when “they focus on notices of eviction … that means they miss people. People can be harassed, or asked verbally to leave.” The sprint team expanded their search to other data that might better meet the needs of their residents, such as existing resources for housing support services. As a result of this process, the team reconfigured their problem statement to focus on the following question: How might we improve the process of finding and obtaining rental assistance for tenants and landlords? Answering this question would get aid into the hands of residents sooner, thereby helping more residents avoid eviction.

Product development

To address San José’s rental assistance challenge, the sprint team decided to create a tool that would make it easier to get funds into the hands of tenants and landlords that needed it most. The team explored three potential options that would do so. First, the sprint team considered creating a one-page application or a text-based portal to streamline the process of applying to both State and local rental assistance. Second, they considered adding features to the State’s current assistance application, such as allowing residents to request documentation or information directly from their landlord, or to electronically ask family or friends for help with finding documentation. Finally, they brainstormed an approach that would compile all relevant City and State rental assistance resources and share essential information that could help tenants and landlords apply for rental assistance.

The team vetted the feasibility of these three options by speaking with State and City stakeholders. The State assistance program declined to share the code base that would have allowed the team to add in features to their application process and streamline the process for renters and landlords. Given these limitations, and the positive feedback from City and community stakeholders, the team ultimately moved forward with the third idea: publishing relevant information about how to apply to State and City rental assistance.

Considering that the research revealed widespread government distrust, confusion about filling out the applications, and a significant digital divide, the team decided that simply adding another digital tool would not be enough to help at-risk residents receive rental assistance. To truly meet the residents of San José where they are, the digital tool needed to be supplemented with in-person support from organizations that residents would trust. Accordingly, the City and Catholic Charities set up pilot pop-up eviction help centers at trusted community locations. Residents could walk in and receive targeted support with their application from Catholic Charities workers. The sprint team then set about compiling data on the locations of these pop-ups so that the digital tool could direct residents to their nearest pop-up location should they require in-person support as they navigated the rental assistance process.

This exploration process took slightly longer than expected and ultimately shortened the team’s time for user testing with the product. However, this due diligence saved time and resources in the long run: rather than building a tool that would be incomplete due to struggles to coordinate with the State, they pivoted to a solution that would meet residents’ needs for a mix of digital and in-person support while sharing public information about the rental assistance process.

Product launch

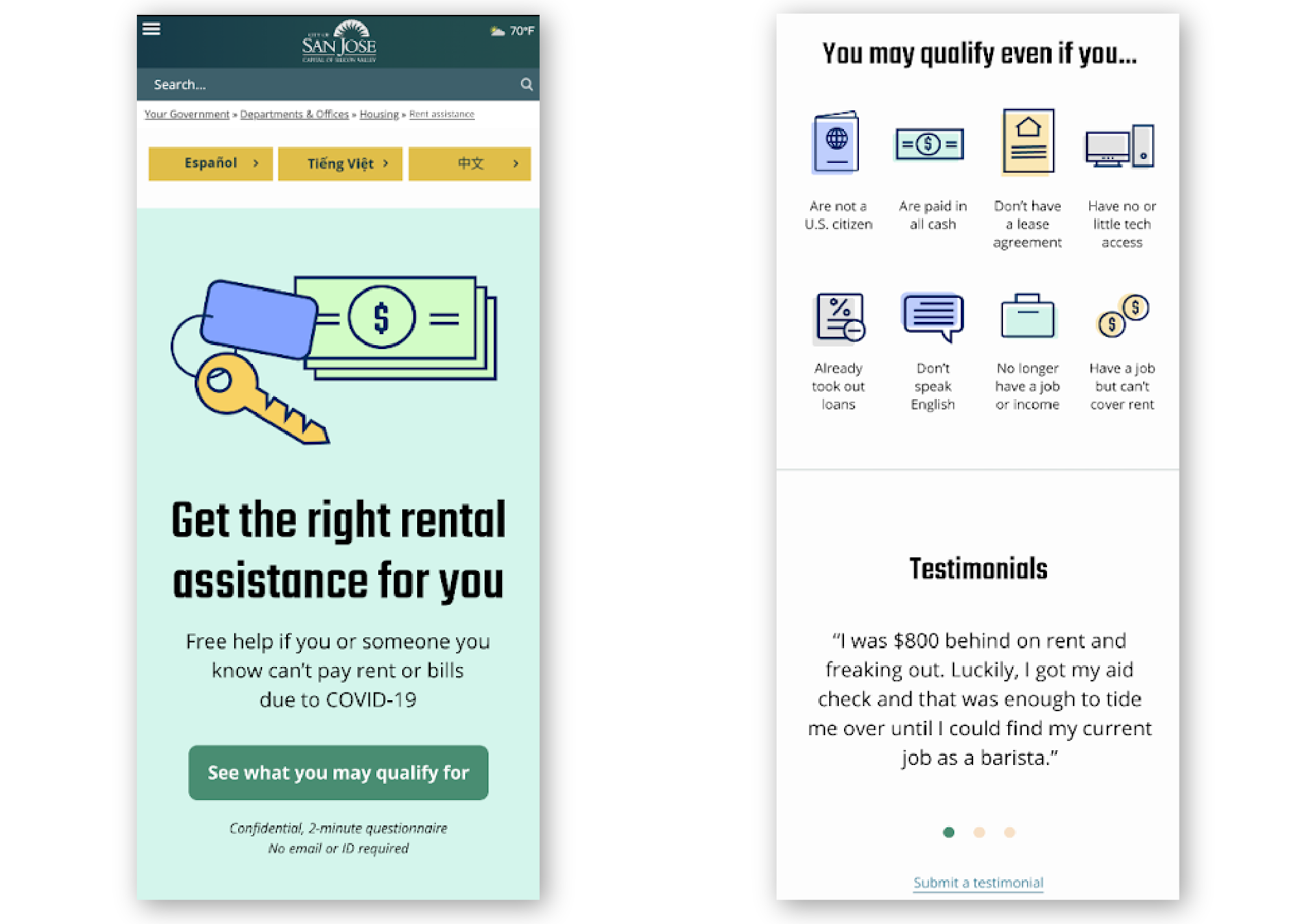

Ultimately, San José developed a City-owned, community co-branded Rental Assistance Finder that makes the emergency rental assistance process easier to understand and highlights community resources that can help to meet additional resident needs. This tool provides an estimate of the rental assistance that residents can expect after applying for aid and publishes data on the locations of in-person pop-up resources run by Catholic Charities to help residents apply. Notably, the Rental Assistance Finder goes beyond simply compiling open data on available rental assistance resources; it also directs people to the aid that is most appropriate for them based on their responses to questions regarding employment, residence, and the documentation and identification they have available. Upon entry, the page directs users (either tenants or landlords) through a short questionnaire that calculates the estimated total aid they may qualify for and highlights specific additional in-kind services that may be helpful. The page also directs users to a nearby popup, enables them to make an appointment, and notes which documents they need to bring to expedite the process. The Rental Assistance Finder will be accessible from both the City’s and Catholic Charities’ websites.

San José's Rental Assistance Finder Prototype

San José's Rental Assistance Finder Prototype

In developing the Rental Assistance Finder, the sprint team leveraged existing code from New York State’s “Find Services” tool, an open-source product developed with support from Google.org Fellows that helps residents find social services and benefits in New York State. This codebase enabled them to start further along in the development process and ultimately include a more robust suite of features than they would have otherwise been able to within the time constraints of the sprint.

Given the magnitude of the digital divide in San José and the broad distrust of government in some communities, the team anticipates that not all residents requiring aid will use the tool. The team expects that the Resource Page will spark word-of-mouth uptake in rental assistance more broadly and is addressing the digital divide barrier by offering in-person support. After launch, the tool will be shared with frontline staff at more than 47 community organizations who support the delivery of rental assistance, starting with Catholic Charities, so they can use the tool to support residents on the ground.

Key takeaways

The sprint experience in San José yielded many helpful lessons for public servants seeking to develop new programs and tools to address housing-related challenges:

Acknowledge constituents’ distrust, and work with residents to improve trust in government services. Instead of ignoring or dismissing sentiments of distrust around government-provided-rental assistance, the sprint team worked to ensure that even those who are skeptical of the government would feel comfortable using the prototype to access aid. With Catholic Charities leading the design of in-person support services, the sprint team designed the product to direct residents to trusted or neutral intermediaries, such as service providers. With Catholic Charities’ design feedback, the team also ensured service providers could use the product themselves. Further, in an effort to reduce resident hesitancy around usage, the team decided to co-brand the resource with both the City and Catholic Charities, change the website’s colors, and add accessible visuals so the tool feels less like a standard San José government website.

Guadalupe Gonzalez Rent Stabilization Program Analyst, City of San José"By strengthening our partnership with Catholic Charities, we’re starting to build that trust. We have to start understanding that as a city government, there are areas that we do well and there are areas that Catholic Charities does well. By working together in a project like TOPcities, it shows the community not only can we work together well, we are building up that rapport, building up that trust together."

Data challenges can be unpredictable, which makes it important to identify what information is valuable to residents early on. Data on rental assistance often crosses jurisdictions, creating barriers in data access. Despite the fact that the sprint team heard from residents that disparate City and State application processes were a key barrier to accessing rental assistance, they could not access the State’s data to analyze assistance delivery times or other key information about the application and delivery process. This limited the prototypes they could ultimately develop. If they had known this in advance, they might have considered additional city data sources beyond information on in-kind services and pop-up centers. As such, the tool highlights data on the locations of in-person pop-up centers for assistance.

Digital solutions should be complemented by in-person resources on housing when they are more helpful. The sprint team discovered that residents at risk of eviction are less likely to have reliable internet access, making it harder to obtain assistance and other important resources. One of San José’s core goals for its product was to ensure that residents most at risk of eviction were able to benefit from the Resource Page. With that said, the tool they ultimately developed requires a considerable amount of digital literacy and access to technology, which many of those most in need did not have. To compensate for this, the sprint team designed the tool so it could also complement in-person assistance efforts, including directing residents to their nearest rental assistance pop-up to complete an application and providing phone numbers for key service providers in their area. As the product owner, the City team is sharing the tool with all community organizations that support the rental assistance programs within the City. Service providers are also being trained to use the tool with walk-in clients.

Case study two: supporting unsheltered residents in Saint Paul, Minnesota

The problem:

Since the start of COVID-19, there has been a tenfold increase in the number of residents experiencing homelessness in Saint Paul. The increase in the unsheltered population and the limited non-profit serving capacity due to social distancing requirements have placed a tremendous strain on the system. As a result, Saint Paul’s unsheltered residents have struggled to access essential resources like shelter, counseling, and other important services. Making matters worse was the harsh cold weather this winter, which contributed to frostbite and encampment fires as a result of unsheltered residents using propane tanks for heat.

Worried about the well-being and safety of unsheltered residents, the Saint Paul sprint team decided to use the sprint to explore the following question: How might the City of Saint Paul and Heading Home Ramsey support providers, the public, and residents experiencing homelessness to connect with services they need at the time they are ready to access those services?

The team:

The Saint Paul sprint team included the City of Saint Paul, M Health Fairview, Google.org, and independent product advising from civic tech expert Noah Kunin, Chief Information Security Officer at U.Group. Public servants from diverse City departments engaged in the process, including staff from the Mayor’s Office, Digital Services, Safety & Inspections, and Innovation teams, which allowed for a rich mix of cross-city perspectives and expertise in the process.

As the community partner, M Health Fairview offered staff from their leadership, data, and patient care teams to provide deep insights on serving unsheltered clients. The City selected M Health Fairview for the sprint after partnering with them through the Heading Home Ramsey Continuum of Care, the County’s system for providing services to unsheltered residents. The CPI and Beeck teams connected the sprint team to product advising support from Noah Kunin who brought civic technology expertise and experience with product development at multiple levels of government, including in the state of Minnesota. Additionally, Google.org contributed product managers, engineers, data scientists, and user experience designers to support with community research, product brainstorming, technical assistance, and product development.

The sprint team had multiple touchpoints with community partners in the Heading Home Ramsey community, a regional coalition that brings together “social service providers, housing providers, philanthropic partners, business, community, government, and citizens working together to create and implement cost-effective solutions to ending homelessness.” This partnership played an advisory role and helped the sprint team connect with residents for feedback.

The sprint:

Problem understanding

To better understand this problem, the sprint team evaluated existing public data on services for unsheltered residents to identify opportunities to publish information that would help these residents and service providers. The team interviewed 30 service providers and unsheltered residents to learn more about the experiences and challenges facing these residents and the people who serve them.

The team also received input from additional service providers by hosting a focus group and using a survey in order to better understand different barriers and opportunities within the service delivery system. These interviews helped the team to better understand some of the barriers that unsheltered residents experience, exposing which points in the journey to housing could benefit from technical intervention. The research process produced these top insights:

Residents desire greater autonomy to access services related to their specific needs. So much of the service delivery system involved variables that were outside of the residents’ control, such as requiring a referral from a caseworker to access a particular shelter or waiting for the approval of a government assistance application. Residents emphasized that barriers to accessing services and aid made them feel like they didn’t have control over their own lives.

Service providers similarly cited barriers to autonomy as a concern: “There is no direct line for clients to call to access [certain] programs even if they are eligible.” Service providers felt frustrated that they were sometimes forced to serve as gatekeepers to accessing services when so many residents urgently needed help. The referral process also made it hard to prioritize the residents who needed greater hands-on support to navigate the system. One service provider shared that because of the referral system, “We spend a lot of time and resources doing work with someone who may be perfectly capable of doing that on their own.”

Having a decentralized system makes it difficult for residents to know where to go for services. Residents shared that they didn’t always know where to go to receive help for their specific needs. Further, when they found a service they wanted, they sometimes were denied assistance because they didn’t meet eligibility requirements. As one of our sprint team members observed: “People have to navigate several different systems, and it's hard to understand their eligibility. This makes identifying and accessing resources challenging and can demoralize [people]. This keeps folks from seeking and accessing the support they want.”

Service providers similarly shared that they also weren’t always aware of the full spectrum of services available. Even when they learned about a new service, they were hesitant to refer clients to the agency if they couldn’t personally vouch for the service itself. As one service provider shared, “I don’t like to send someone somewhere to something I haven’t experienced. If I didn't feel like I wanted to go there, I wouldn’t send someone there.”

Residents do not have access to real-time information on service availability, which can have dire consequences. By interviewing residents and service providers and examining available local data on homelessness rates and services, the team discovered a number of barriers. They realized that data relating to homelessness was often siloed and inaccessible. It was also difficult to find accurate real-time data on service availability. Not having access to real-time information on service availability can have significant consequences for residents. As one of our City team members shared: “Accurate information for [residents] is critical to identifying and aligning timely services to meet their needs. [Residents] are frustrated/ill-informed because they do not have complete/real-time access to information. This may result in a [resident] making a misinformed and life/safety related decision.”

By engaging in a robust problem-scoping process, the team realized that any solution they designed must promote autonomy for unsheltered residents, remove bottlenecks in service delivery, centralize service information, and increase publicly available data on services. The process helped to increase representation of the community’s voice and developed the City and community partner’s capacity to engage with community members and social service providers when developing future programs. With this, the sprint team moved forward with their original problem statement: How might the City of Saint Paul and Heading Home Ramsey support providers, the public, and residents experiencing homelessness to connect with services they need at the time they are ready to access those services?

Product development

After processing research insights and conducting a series of collaborative brainstorming sessions, the sprint team decided to develop a centralized resource hub that makes it easier for residents experiencing homelessness to discover and access information on essential short-term services in their community, such as low-barrier shelter beds, lockers, meals, and laundry. Low-barrier shelter beds were of particular interest for the sprint team, given that more accurate and real-time information on bed availability could increase residents’ ability to independently and preemptively plan where they would prefer to stay overnight.

The team initially began drawing out ideas for this tool but came to realize that there was a pre-existing tool, ShelterApp, that might be able to meet their needs. ShelterApp already offered information on the locations of shelters and other essential services, public transit directions to services based on an individual’s specific location, as well as hours and contact information for services. It just needed to be populated with information from service providers in Saint Paul. Further, ShelterApp agreed to open-source its code using a CreativeCommons BY license, which meant that the team could use the existing codebase to create a version for shelters and key unsheltered services within Saint Paul’s city limits.

Ultimately the team decided that partnering with ShelterApp would enable them to roll out a better-developed product to the community and would make it possible to scale the open-source product across Ramsey County so other members of Heading Home Ramsey could eventually use it to share information and data about their services. Had they elected to build their own app instead of partnering with ShelterApp, they would have finished the sprint with a less-developed product, higher expenses, and much higher upfront technical needs.

The team tested ShelterApp with service providers and residents and received highly positive feedback. As one service provider summarized, “The biggest win is user accessibility and information without having to go through a ‘gatekeeper.’” Based on community feedback, the team developed a set of modifications that would help ShelterApp better fit the needs of the local context. These modifications included app features such as providing photos of shelter spaces, adding in step-by-step directions on how to access a bed upon arriving at a shelter, and building in the app’s future capacity to show real-time data on bed availability.

Drew Nelson Digital Services Manager, City of Saint Paul"The TOPcities sprint process really hit the importance of doing the direct interview with the “users”, from both the IT and Services perspectives. Working collaboratively with the people who will utilize that service to define what they need and how this will support them was a very impacting experience, and we’re building a better product and delivering a better service as a result."

These modifications offered a number of benefits to residents. Providing photos of shelter spaces would enable residents to see a space before they showed up, which could help them feel more comfortable with using it. The step-by-step directions on accessing shelters would make it easier for residents to know what they needed to do to get a bed in advance. This could help them avoid frustrations like showing up to a shelter only to learn they were ineligible. At a more systemic level, this feature would also expand publicly available data around the process for accessing beds at different low-barrier shelters. Lastly, enabling residents to see bed availability could help them to better prioritize where to go for shelter. Given that residents were often commuting to shelters by foot or bus, this feature was key for saving them time.

Product launch

When the sprint initially launched, the team wanted to understand how to make it easier for unsheltered residents to connect with essential services at the time they are ready to access those services. The sprint’s final product, ShelterApp, provides the foundation for fulfilling that mandate by providing a centralized platform for unsheltered residents to search and learn more about the essential services that they need, whenever they need them. The team hopes that the product will eventually allow residents to book shelter beds from the app, making it easier for residents to ensure they have an indoor place to sleep overnight as desired. As the product owner, the City team is now working on collaborating with Ramsey County in order to expand the app’s reach to the County’s contracted providers and the rest of Heading Home Ramsey.

Saint Paul's ShelterApp Prototype

Saint Paul's ShelterApp Prototype

While ShelterApp’s influence in Saint Paul and Ramsey County remains to be seen, it shows promise for broader impact. As the team noted during the research process, data relating to homelessness was often inaccessible across partners and real-time data on service availability was not publicly available. ShelterApp has the potential to serve as the initial infrastructure for an open data system that improves service delivery and access in Ramsey County. It also provides a foundation for future digital innovation in addressing and reducing homelessness.

Key takeaways:

The sprint experience in Saint Paul yielded many helpful lessons for public servants seeking to develop new programs and tools to address housing-related challenges. These ideas are shared below:

Community members are one of government’s greatest assets when trying to address housing challenges. While researching the problem, the team saw that service providers and unsheltered residents were the best resources for understanding systemic barriers and residents’ needs. For example, the team originally assumed that they would develop a tool that would make it easier for service providers to help residents seeking shelter. They learned from residents and service providers that any tool the team developed must enable resident autonomy in the process. This major insight caused the team to prioritize developing a tool that anyone could use to discover and access services relating to being unsheltered. Recognizing the immense value of the community’s perspective, the sprint team later invited service providers to join sessions to brainstorm design-based solutions and eagerly sought community input when developing the product. This more collaborative approach increases the likelihood that the team’s product will meet the needs of residents and those who serve them.

Build buy-in from high-level stakeholders early and often. Homelessness is a complex cross-jurisdictional challenge that requires support from diverse stakeholders. As such, the Saint Paul sprint team benefited from having the deputy mayor and top leadership from M Health Fairview actively engaged in the weekly sprint activities. Frequently engaging with high-level city and community leaders enabled the team to get early internal buy-in for their solution. By the same token, the team experienced the challenge of not engaging with county leaders focused on homelessness early enough in the process. It was important for the team to get the County onboard because the County is responsible for collecting data on homelessness and distributing funding to service providers. The team later realized that because of these responsibilities, the County was better positioned to serve as the product owner than the City. Engaging high-level stakeholders from the County earlier in the sprint may have made it easier to initiate product ownership conversations with the County.

You don’t have to start from scratch when designing innovative housing solutions. Given that many communities across the United States face housing challenges, it is beneficial to see what other products currently exist before developing a new product from scratch. Saint Paul was able to launch a significantly more developed tool by leveraging a pre-existing app and adapting it to meet local needs. This made the app more immediately usable for unsheltered residents and service providers. In choosing this path forward, it is important to note that the decision to select a pre-existing solution was informed by the team’s conversations with residents and service providers during the problem understanding phase. Further, the team didn’t simply use ShelterApp; rather, they partnered with ShelterApp to adapt it to the local homelessness context. This meant that the product was better positioned to serve resident needs.

Key lessons

In addition to the key takeaways gained from the sprint teams in San José and Saint Paul, there are broader programmatic lessons that may be helpful for local governments seeking to apply best practices from the TOPcities pilot program:

Governments can adopt new practices quickly without forsaking intentionality. There is an implicit assumption that moving fast and doing robust community engagement are at odds. The TOPcities program pushes against this assumption by limiting the time government has to understand and address a public challenge. While this does force sprint teams to make decisions much faster, it also encourages iterative engagement with residents over time. In other words, governments can seek out resident input in meaningful but light-touch ways at each stage of the process, thus keeping residents involved while prototypes and projects evolve. Our government partners saw the benefits of this approach, particularly in how it helped them to make quick progress on difficult issues. As one of our sprint participants from San José shared: “Partnering with a community-based organization to center community perspective has been so valuable, and a pleasant surprise has been the speed at which we tackled gaining community survey results. I know this sprint was meant to do just that, but I'm still impressed.”

Guadalupe Gonzalez Rent Stabilization Program Analyst, City of San José"What the TOPcities process really did was show that working together to solve a problem not only is possible, but it’s feasible in a pressurized environment."

Ground yourself in the data that exists, with an eye toward helping to make the data you want available in the future. One of the greatest challenges for sprint participants was the lack of prepared, clean, or structured data for their projects. In Saint Paul, the team realized that while there was data available on homelessness, it wasn’t bulk data that could be easily analyzed to generate insights. After speaking with community residents, teams found that the data they needed was simple information about shelter locations, hours of operation, and visual data like photos of shelters that would help them set expectations about available locations. A Saint Paul City employee emphasized the need for better data in the long run, sharing that “There is a lot of data that exists but is [not] easily accessible or doesn't measure important outcomes.” This realization influenced the Saint Paul sprint team to design a product that would help make initial data about shelter services accessible while driving the Heading Home Ramsey continuum toward a tool that would generate better data in the future.

Travis Bistodeau Deputy Director, Department of Safety and Inspections, City of Saint Paul"You need to think about the long-term maintenance, sustainability, and support of technology solutions. Bringing in service providers to look at the backend of how the app would work and would it be an easy thing for them to support and maintain going forward, is not something I thought about as we were building it up. When building a pilot project I often think about how to get the plane off the ground, but not how to keep it in the air long-term. That’s something we thought about on the front-end.”

Cross-sector collaboration leads to innovation and supports upskilling across sectors. By bringing together government leaders, community practitioners, and technology experts, team members learned new ways to think about open data, product development, and community engagement. This diversity of perspectives pushed government teams to reevaluate their understanding of the root problem, encouraged technology teams to work within complex political environments, and gave community partners a greater voice in developing tools they would actually use. Fundamentally, it re-shaped the dynamic of cross-sectoral work, moving from a transactional approach where input is simply shared with city decision-makers to a more comprehensive partnership where all parties have an equal opportunity to shape the outcome. This experience taught sprint participants new skillsets in innovation and product development that we expect will be sustained over time. One of our community partner team members summarized the benefits of this approach, sharing that their biggest learning was the “power of bringing a group of people from different sectors together and new approaches to finding solutions.”

Fred Tran Rent Stabilization Division Manager, City of San José“What helped me the most was seeing how community-based organizations that do have community trust, that do have that relationship, are able to build upon that, and we are able to leverage them. We may not be able to communicate it directly, but they are. They’re able to offer that trust and that relationship from a more solidified standpoint and ultimately that’s what gets these people engaged into the process and gets them the resources that they need."

A product is rarely the sole solution to an entrenched social issue. The products developed during a sprint should serve as part of a broader approach to addressing a systemic challenge. The Saint Paul team inspired this insight by deciding to develop the product as a supplemental part of Heading Home Ramsey’s comprehensive approach to alleviating homelessness, which involves a longer-term effort to centralize essential data about available services. San José’s tool is also part of a broader effort to integrate data across City and community providers so that they can more quickly deliver aid to their communities. Both teams are already planning to transition the tool to serve their overarching, strategic goals when the sprints are over. This foresight illustrates the value of anticipating that these products will evolve over time to meet new resident needs as part of governments’ broader strategies in collaboration with their trusted community partners.

Rachel Walch Innovation Consultant, Office of the Mayor, City of Saint Paul"I knew there was going to be culture change involved in the TOPcities sprint, but I didn’t anticipate such big system changes needing to happen for the longevity of the tool to operate in the way residents and providers want it to operate, like securing their own bed for the night and real-time communication with providers - that’s not only culture change but also systems change. If we want to get to a place where this is possible, which residents and providers said they wanted, we have to change how the system operates and that is going to be challenging."

Program analysis

As evidenced by each case study’s key takeaways and the broader key lessons, the TOPcities pilot offered many opportunities for learning and growth. The Saint Paul and San José sprint teams showed tremendous persistence, creativity, and adaptability throughout the sprint as they tried out new approaches and skills. Both cities developed meaningful products and capacities that we hope will lead to innovation in other areas of their work.

As with all pilot programs, several elements of program design worked well, while others provided opportunities for improvement in future cohorts. The following subsection provides a brief analysis of some of the highlights and opportunities to iterate upon moving forward:

Centering community voices: The TOPcities sprint gave local governments an intentional space to think and act differently relative to their traditional practices. This meant that public servants listened and learned from the community first, and then designed a tool to meet those needs. This marks a significant shift in how cities traditionally design policies and initiatives. When we asked local government participants how their perspective on designing solutions with their community changed through the program, one shared that the sprint “reinforced [the] importance of collaboration and co-creation from the outset with those with lived experience.”

Given the benefits of this programmatic design feature, we plan to further amplify coaching to support more robust community ownership of design and development processes in future sprints.

Leaving space for iteration: We launched the sprint as a four-month process acknowledging the intrinsic value of a design sprint: it forces participants to iterate quickly and focus deeply to finish one important priority in good time. A detailed description of the benefits of this time-boxed approach is described in Key Lesson #1: “Governments can adopt new practices quickly without forsaking intentionality.”

While designing this initiative as a sprint clearly achieved its desired impact, teams would have benefited from slightly more time for early-stage team-building, onboarding, and having space to navigate political winds, make mistakes, and iterate accordingly later on. Future TOPcities programs will continue as a design sprint, with two additional weeks, and a robust pre-work phase with additional CPI and the Beeck Center coaching to support these needs.

Expanding product advising and coaching: Navigating a design sprint is difficult, particularly for team members who are new to the design process. CPI, the Beeck Center, and the product advisors provided significant coaching throughout the program, which exposed public servants to new strategies for analyzing and addressing systemic challenges, collaborating across sectors, centering community, and leveraging technology when designing solutions. The benefits of this approach are clear. One city official shared that the sprint “will make me advocate more clearly for longer-term development plans and [community] engagement, and hopefully I can use this project as an example for why taking the time to do this right instead of ‘building the plane as we fly it’ is beneficial.”

Building on this foundation, future cohorts will continue to include extensive coaching in human-centered design, open data, product development, and strategies for centering community, including in-house product advisory support from the Beeck Center.

Building stronger cross-city connections: Teams significantly benefited from collaborating and sharing ideas across sectors, as evidenced by Key Lesson #3: “Cross-sector collaboration leads to innovation and supports upskilling across sectors.” Notably, across both teams, there are early signs that these cross-sector connections will continue past the conclusion of the sprint, particularly as cities and community partners collaborate to roll out these tools. Team members from Google.org have similarly expressed interest in continuing to support the products’ continued development post-sprint.

While the cross-sector element of the program was a particularly strong design feature, there is an opportunity to strengthen program design around promoting cross-cohort connections. Future iterations of TOPcities will magnify the benefits of the learning network by increasing opportunities to reflect and share ideas across places and with external subject matter experts.

Conclusion

The TOPcities sprint launched in February 2021 at a point where COVID-19 vaccine availability was still limited, daily case rates were high, and many local governments and residents continued to face challenges resulting from the pandemic. When the teams launched their products on June 18th, the landscape in the United States had dramatically shifted. At least 55 percent of U.S. adults over age 18 had been fully vaccinated, and infection rates had significantly lowered to a seven-day average of 11,630 cases per day. This moment of progress is a cause for celebration, gratitude, and recognition of those we have lost.

As the United States continues to re-open, local governments will be asked to adapt in new ways. We believe that the skills Saint Paul and San José gained during the sprint will enable them to adapt as their local contexts shift and that they will be able to apply their new strategies for analyzing and addressing systemic challenges, leveraging technology and open data to develop solutions, collaborating across sectors, and most importantly, centering communities.

Looking forward, we’re excited to see how San José and Saint Paul continue to roll out their products to the community, iterate upon those products, and incorporate them into their broader eviction and homelessness prevention strategies. At CPI and the Beeck Center, we are also entering our own internal process of iteration on TOPcities. As a pilot program, TOPcities was our own version of a minimum viable product. We are now entering our process of iterating on the program to amplify skill development, support mindset shifts, and scale our impact. We’re excited to see how TOPcities evolves to have a deeper and broader-reaching impact.

Download the TOPcities report and sprint toolkit

Does your team want to build data-led solutions to pressing community challenges? Download the complete TOPcities report and sprint toolkit for step-by-step instructions to run a TOPcities sprint in your city.

Click here to read the sprint toolkit and report online.

You may also be interested in...

Mexico City's ProAire programme

National portal for government services and Information: gob.mx

Urban agriculture in Havana

The eco-friendly façade of the Manuel Gea González Hospital tower in Mexico City