From ‘Water’ to ‘Why’: New Orleans’ Resident Engagement Journey

Article highlights

.@CityofNOLA @MayorCantrell has been part of @BHcityleaders to inspire & strengthen city leaders, equipping them w/ tools to lead high-performing, innovative cities

Share article.@CityofNOLA @MayorCantrell 'Project Why' aims to proactively communicate w/ residents & meet them where they are at, in order to rebuild #trust

Share article"Ultimately, @CityofNOLA thinks it gives out tons of info & residents think they aren't receiving any. Both are true because there is a disconnect between residents and the City"

Share articlePartnering for Learning

We put our vision for government into practice through learning partner projects that align with our values and help reimagine government so that it works for everyone.

From November 2019 to December 2020, New Orleans participated in The Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative, a program that seeks to inspire and strengthen city leaders and equip them with the tools to lead high-performing and innovative cities; the Centre for Public Impact implements the Innovation Track of the program. Over 14 months, members from various City departments and agencies formed an innovation team to tackle flooding in New Orleans after a ballot measure to fund infrastructure maintenance failed. By engaging deeply with residents, the City understood that the ballot measure failed because of an underlying problem: residents deeply mistrust the City. With this new problem in mind, the City endeavored to rebuild trust through a reimagined approach to communications. The resulting initiative, "Project Why," aims to proactively communicate with residents and meet them where they are at. The project is currently in its pilot phase and will continue to evolve based on community feedback. If successful, New Orleans sees great potential to implement "Project Why" across City services, ultimately building a renewed reservoir of trust with residents and laying the foundation to more collaboratively and productively identify and address community problems.

Our Problem: Floods, floods, floods

Over the past five years, New Orleans faced an unprecedented number of floods due to the high volume of rain events. Flooding is the result of two core problems: 1) the City infrastructure is aging and outdated, with a substantial amount of the infrastructure being over 80 years old, and 2) climate change is driving an increasing number of cloudbursts – extreme short-term rain events which can drop as much as five inches of rain in a couple of hours.

Our Initial Solution

The Mayor and the City Council worked together to create a solution: a property tax ballot measure for infrastructure maintenance. The new tax dollars were to be split between the City's Department of Public Works, which is largely responsible for building and maintaining water management features like retention ponds and the City's public water utility, and the Sewerage and Water Board which is responsible for drainage. When all was said and done, however, residents resoundingly rejected the new property tax.

Talking to Residents: The Autopsy of a Failed Proposal

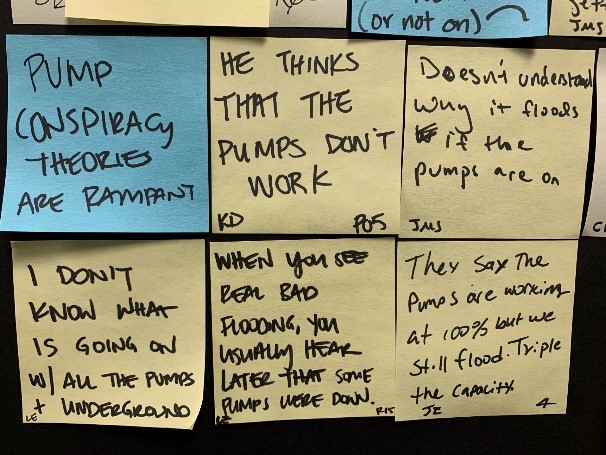

We knew that residents did not want to live with flooding – they certainly complained enough about it- but the failed ballot initiative told us that they were not willing to pay to fix the problem. This was an incongruity we needed to understand. To find answers, our team conducted a series of stakeholder interviews.

Our interview methodology prioritized truly meeting people where they were. We went to homes and businesses. We went to waiting rooms at City Hall's permitting office and our Sewerage and Water Board. We even intercepted people in parks and along the street. Ultimately, the people gave us a clear and consistent message: "The City is corrupt and incompetent. Giving you more money won't help." It was utterly disheartening.

Incompetence Board

Incompetence Board

We were floored. The City team knew there were trust issues with residents, but none of us realized how deeply rooted and pervasive the problem was. This was not just some or most people. Every single person we interviewed told us at least one story about why they did not trust the City to solve the problem.

This started us down a long road of introspection, and we realized that the facts didn't look good. In the last ten years, some of the missteps we had include:

A previous Mayor and a Congressman were both found guilty of corruption

The Sewerage and Water Board failed to disclose known issues with the functionality of our drainage system after a rain event caused widespread flooding

The local power company paid actors to fill City Council meetings in support of a new power plant

Huge numbers of residents were displaced for “Economic Development”

Roads were constructed over one foot above residents’ driveways, making their homes inaccessible

A large portion of the City’s water system became depressurized for hours when multiple Sewerage and Water Board employees fell asleep at the job

Residents had regular, personal interactions with the City that they believed simply do not make sense

When we laid out the facts, the message we heard from residents was consistent and clear. Their distrust was rational and evidence based.

The City team knew there were trust issues with residents, but none of us realized how deeply rooted and pervasive the problem was.

Reframing the Problem: First communicating, then the floods

Recognizing that getting buy-in from residents would be the first step to finding a solution for our water problems, the team shifted gears to first prioritize rebuilding trust with residents by improving the way we communicate with each other.

Our administration focused on increasing transparency and accountability. Despite major progress and a robust communications campaign to highlight our efforts, the gains went largely unnoticed by residents. People didn't know about the datasets we regularly publish online, the dashboards we set up, or the roadwork maps published on the City website.

On the flip side, the City also struggled to hear residents. People gave us a lot of information – they called and e-mailed us all the time – but that information wasn't getting where it needed to go within the City government for us to address their concerns adequately. All too often, responses to resident questions felt dismissive or placating – while technically correct, responses were generally disconnected, indifferent, or unconcerned about what the resident needed. This disconnect prevented the City from showing residents that it can be competent and dependable. While the systems for residents to provide input were designed to build trust, the City's inability to consistently address concerns resulting in the opposite effect: we were further eroding trust.

Infrastructure projects were a prime example of the City and residents talking past each other. From residents, the City received a lot of feedback on infrastructure projects in the form of phone calls and questions. But the right people weren't necessarily receiving that feedback. From the City, residents received a variety of communications in a variety of forms - a postcard about the project (sometimes) sent to their homes, a digital map and PDF presentation available on our website, and a presentation given at public meetings (as required by law). But those postcards had very little information about what the project work would entail, the information on the website wasn't necessarily self-explanatory, and the public meeting was only helpful to the small portion of residents who had the time and ability to go to a meeting. Ultimately, the City thinks it gives out tons of information, and residents think they aren't receiving any. Both of these things are true because there is a disconnect in the information flow between residents and the City.

To solve this problem, we understood that we needed to redesign how we communicated with residents so that it put their reality first. So we asked ourselves:

What information do residents want and need?

How would they like to receive that information?

Ultimately, the City thinks it gives out tons of information, and residents think they aren't receiving any. Both of these things are true because there is a disconnect in the information flow between residents and the City.

The question “Why?”: A New Theory on Communications

Efforts to resolve these questions ultimately led us to prototype "Project Why." The goal of "Project Why" is to bring information that residents want and need to know about infrastructure projects directly to them when, where, and how they want that information. To ensure we were actually meeting these goals, we worked with residents to design and iterate on "Project Why," so it has evolved substantially since its conception to what it is today.

"Project Why" started with the concept of a "Why Button" that residents could press to get more information. The "Why Button" was first conceived as a digital tool – it would be placed in press releases and other digital communications and allow viewers to access and request more information if desired.

As we did more research, however, we realized this was not proactive enough. We needed to bring information to the residents in a way that did not rely on them needing to seek it out. So the "Why Button" transformed from a digital button, which would help only the limited number of people with digital access who choose to search the City's website or press releases, to a physical presence in the impacted neighborhood. That is how the "Why Button" became a physical sign.

But we didn't stop there; in prototyping the sign, we realized details really matter. For too long as government, we have taken our monopoly for granted. We create a sign template, replicate it, stick it in the ground, and forget about it. However, through conversations with residents, we realized the design and content of signs really matter to people. Residents gave us invaluable feedback leading us to improve content, design, materials, and even working to establish non-language versions of signage that can be universally understood.

By the conclusion of the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative Innovation Track, the team is still exploring and testing these ideas – are we explaining things people care about? Are we just better at articulating systems and processes that don't actually make any sense? Do we know how we show up in peoples' lives? When or how do we gain (or lose) their trust?

The Future of Project Why

We are hopeful that the "Project Why" signs' visibility will make clear the City's new commitment to proactive communication and reaching people where they are. We envision "Project Why" as a larger citywide reimagining of how the City interacts with the public and consumes feedback. We want all departments to identify pathways to intake residents' concerns and funnel them into generating more proactive, efficient, and effective communications and interactions with residents.

We believe by shifting the underlying philosophy of how the City interacts with the public, we can build a renewed reservoir of trust with residents. The renewed trust will be built upon the back of open and proactive dialogue, and a collaborative effort to create solutions to community problems.

You may also be interested in...