Four key insights for improving regulatory practices in Greater Manchester

Article highlights

.@CPI_foundation has been working with @greatermcr to understand how regulation & inspection might improve services for people. In this article, @Yu_Lin_Chou shares key insights from this work.

Share articleWhat's preventing regulation from driving learning and improvement? In this @CPI_foundation article, @Yu_Lin_Chou identifies barriers at the level of person, practitioner, system and culture.

Share article“The way accountability is set up isn’t working––it doesn't incentivise responsibility”. So, how could regulatory practices be improved so people are understood & practitioners feel empowered?

Share articlePartnering for Learning

We put our vision for government into practice through learning partner projects that align with our values and help reimagine government so that it works for everyone.

Regulation is a powerful tool governments can use to achieve policy objectives. It helps service providers understand how to improve the quality and safety of services and, in doing so, drives learning and innovation. However, approaches to regulation can also create barriers to making services better for people.

In partnership with The Kings Fund, we have been working with the Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA) to understand how regulation and inspection might improve services for those experiencing multiple disadvantage. Since 2021, we have launched a community of practice and explored what more collaborative regulatory practice could look like.

Last month, we brought together practitioners from Rochdale and Oldham, and inspectors and regulators from the CQC and Ofsted, to co-design experiments that could enable better ways of working together. This is the first attempt within the UK to bring together a range of regulators with practitioners from local authorities.

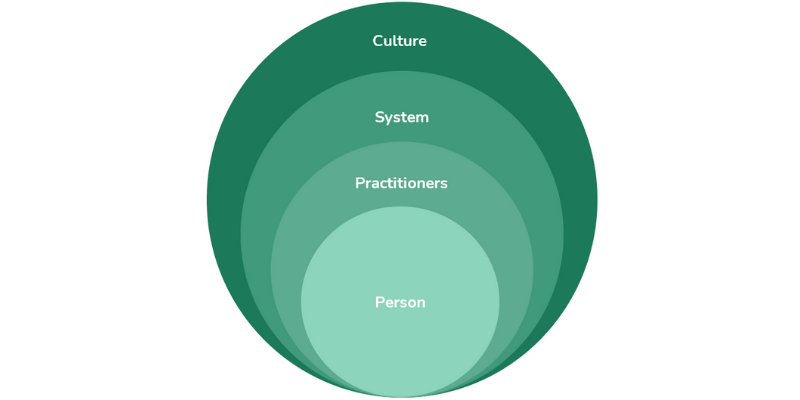

Through this work, we identified four key barriers – at the level of person, practitioners, system, and culture – that currently prevent regulation from driving learning and improvement.

Person: Inspections focus on the providers, not the person

“We are not seeing the person outside of the ‘to-do list’––we are not seeing the individual.”

The way inspection currently operates undermines inspectors’ ability to focus on individuals’ experiences and needs. Their main tasks of assessing the quality and safety of services against national standards drive their attention almost entirely to the providers. This means they often neglect the people that services are meant to serve. In addition, people tend to be seen as another item on the “to-do list”. As one practitioner pointed out: “We need to think about how to get people ‘seen’ by the system”. Another attendee shared a case study that illustrates the challenge.

“There was a case in our locality where a man facing multiple disadvantage (physical disability, criminal justice involvement, and substance misuse) was asked to attend 6 appointments on the same day he was released from prison to access housing and medical support.

Having given up on those tasks, he was later found on the street by a MEAM worker. He stated that he would hand himself into the police for breaking his conditions, as completing the tasks were too hard given his mobility issues and financial situation.”

Without any help or financial means to commute, he was effectively “set up by the system to fail”. If services could see him as a person with complex needs and consider his intersectional disadvantage, they would have been better equipped to centre the design and delivery of services around his needs, rather than demanding him to adjust his needs around services.

Practitioners: Practitioners are not empowered to trust their judgments

“The way accountability is set up isn’t working––it doesn't incentivise responsibility.”

Even when the system attempts to “see the person”, it does not guarantee that practitioners feel supported enough to respond to their needs. That is, where accountability currently lies does not incentivise responsibility and collective bravery for frontline workers to trust their professional judgement and take positive risks.

What exacerbates this is a lack of clarity around the legal basis for practitioners to take certain actions, such as sharing information with other services to provide continuity of care. This ambiguity creates a “better safe than sorry” culture and an atmosphere of despondency and inertia.

The burden of regulations, or sometimes “overregulation”, on the statutory providers, creates a phenomenon in which unregulated service providers sometimes have more power to provide the support people need. In the case mentioned earlier, the person was eventually supported by an unregulated practitioner to attend probation appointments and find accommodation. This demonstrates that the way regulation and accountability currently operate is no longer fit for purpose in a complex, integrated, and increasingly devolved world.

System: A lack of collaboration inhibits a system-wide response

“It’s frustrating. Some barriers feel like simple and obvious things if we had coordinated.”

On a system level, the relationships between inspectors, regulators, and practitioners are often described as broken. The siloed nature of their interactions often results in the inability of services to respond to complexity.

As the case study reveals, everyone––from probation to homelessness services––“technically” did their job by inviting the person released from prison to appointments. Yet, the actors collectively made it impossible for the person to complete these requirements. These gaps in the system demonstrate the failure of service providers to coordinate effectively and provide holistic support centring on those facing multiple disadvantage. This pattern repeats itself across all areas of public services.

All actors must be actively enabled to collaborate better in a system-wide approach and avoid situations where people fall through the gaps. Iit is therefore crucial to ensure the involvement of people experiencing multiple disadvantage, whose participation, knowledge, and experiences should be at the forefront of service improvement and design.

Culture: A culture of fear around inspection impedes improvement

“We should celebrate progress together, not just being chased over and told off.”

In addition to the more formal barriers in the system around regulation, accountability and inspection, there are also barriers around culture. Inspection is often associated with the words “criticism” and “fear”, and can stir anxiety among practitioners. This culture of fear prohibits productive relationships and service improvement. The recent event around school inspections in Reading highlighted the challenging relationship that inspectors and service providers can have and the “intolerable stress” that can sometimes be placed on practitioners.

Practitioners want to have a positive and trusting relationship and a culture of collective learning with inspectors to make inspection visits worthwhile, as opposed to being “another thing to deal with” deprived of learning potential. One practitioner framed the challenge by asking: “Is there a safe place where regulators can genuinely ask frontline workers: ‘What do you feel most helpless about?’”. This is the level of trust that we hope to arrive at eventually.

Next steps: Experimentation

After identifying barriers, group co-created and committed to taking forward two experiments to unlock regulation’s potential:

Setting up a Public Service Improvement Partnership and an operational taskforce to create an alternative framework to regulatory practices. Centring on improvement in Rochdale, the group aims to bring together CQC, Ofsted, HMIP, academics and other stakeholders to reimagine and experiment with alternative frameworks to regulatory practices. The local task force will ensure people using the services are listened to and engaged.

Initiating an Action Research Programme to understand the evidence for better relationships between inspectors and providers. Led by CQC, the group committed to working with Rochdale, the Changing Futures programme, and Ofsted to build an evidence base for collaborative approaches.

As we continue exploring more collaborative approaches to regulatory practice, we will also feed our learning into a wider National Steering Group. This group consists of leaders from the Department for Levelling Up, Housing & Communities (DLUHC), among others, which we hope will help inform more significant change across sectors and localities.

We are excited to keep working with partners to take these experiments forward. We would love to speak with you if you are working on related topics or would like to be involved in this learning journey.

Written by:

You may also be interested in...

Conversation, culture, and collaboration: building community hubs in Redbridge