Eliminating Pay-for-Play in New Jersey

The initiative

Although civic groups did make steady progress in winning public support for reform, the state legislature did not pass enact any legislation because Democrats and Republicans alike relied heavily on contractors' donations to fund their electoral campaigns.

However, in 2004, outgoing governor, James E. McGreevey, signed an executive order. His successor, Governor Codey, carried forward that momentum and enacted a state law that made the content of the order permanent. In 2006, the New Jersey legislature enacted the Prohibition on Business Entity Contributions (N.J.S.A. 19:44A-20.3 through 20.25), one of the strongest anti-pay-to-play laws in the United States, and several other states followed its model. Under successive governors, New Jersey continued to review the legislation and make changes to it through to the end of 2012.

The challenge

Called “pay-to-play” by the media and citizen groups, it was a tradition in New Jersey to award government contracts to businesses based on their cash donations to political parties rather than on objective merit and value for money. The practice cost taxpayers vast sums of money, running into millions of dollars during the 1990s.

Well known in the US for its levels of political corruption, the State of New Jersey was “particularly vulnerable to procurement corruption” because of the interaction of three conditions: the state's concentration of power in its governor, its weak laws on disclosure of lobbying, and its highly flexible procurement rules. [1]

In the late 1990s, civil society reformer Harry Pozycki began a grassroots campaign to eliminate pay-to-play. He advocated regulations at the state and local level that would bar companies who had made financial campaign contributions from being awarded public contracts in New Jersey.

While procurement overspending has never been quantified, civil society groups estimated that contracting costs were at least 10 percent too high because contractors built the cost of political contributions into their bids. The Citizens Campaign estimated that more than US$1 billion a year was wasted on single tenders and other favours. They drafted the text of a bill that they hoped would eventually go through the state legislature.

The public impact

The stakeholders engaged in the reforms were Governor McGreevey, Governor Codey, the New Jersey state legislature (the 40-member Senate and the 80-member General Assembly), the Citizens Campaign and both political parties:

- Governor McGreevey passed an executive order for the legislation immediately before his resignation. Acting governor, Richard J. Codey, then played a vital role in converting the pay-to-play order into law.

- Media commentators criticised lawmakers who were blocking the bill for being weak on ethics. Codey called the senators back for a special session to vote again, and it passed 34-0.

- Citizens Campaign was active through out the designing and pre-implementation period and produced the first draft of the legislation.

- Both political parties opposed the law in private, but due to its popularity with citizens, they had to support it in public.

Stakeholder engagement

When the draft bill was introduced, it was passed in the Senate but was first stalled and then rejected in the Assembly, Governor McGreevey being initially against the bill. However, it was later through his commitment of and that of his fellow-Democrat successor, Governor Codey, that the pay-to-play legislation was enacted.

There was systemic problem: both the Democrat and Republican parties were reluctant to pass legislation that would inevitably deprive them of large tranches of funding. It therefore required the commitment of individual politicians to overcome those hurdles.

Political commitment

Governor McGreevey, who started the anti pay-to-pay laws through the 2004 executive order, was elected in 2001 and took office in 2002. Elimination of pay-to-play was a core issue of his election campaign.Public confidence

The objective of the whole initiative was clear and specific, i.e., eliminating the pay-to-play political tradition in New Jersey. It was the clear objective of the draft bill prepared by Citizen Campaign, the nonpartisan organisation which took the initiative in the beginning.

The objective remained the same throughout its passage from a campaign group's idea to legislation. Despite the different challenges in terms of feasibility and political support, the objective continued to be clearly stated and refined over time.

Clarity of objectives

The objective of the whole initiative was clear and specific, i.e., eliminating the pay-to-play political tradition in New Jersey. It was the clear objective of the draft bill prepared by Citizen Campaign, the nonpartisan organisation which took the initiative in the beginning.

The objective remained the same throughout its passage from a campaign group's idea to legislation. Despite the different challenges in terms of feasibility and political support, the objective continued to be clearly stated and refined over time.

Feasibility

Before drafting a New Jersey pay-to-pay bill, Citizens Campaign had evaluated existing regulatory systems in various states and federal agencies. They sought to avoid what they saw as the unnecessary bureaucracy that other pay-to-play legislation invoked. For example, each alleged violation of such legislation required an administrative or judicial process for it to be assessed. The group decided that the solution “was to build a regulatory trigger into the procurement contracts, which were legally binding documents”.

The 2004 executive order was based on this model. However, it was found to be unconstitutional because it violated several federal laws and regulations and was considered to be fiscally infeasible.

The 2006 legislation passed by Governor Codey closely followed the language of McGreevey's executive order, with an exception for instances when its application would violate federal laws or regulations. It was legally as well as fiscally feasible, but still there were some loopholes: for example, employees and partners with stakes of less than 10% in a business could make contributions without affecting their eligibility for state contracts. However, in a statement at the time, Governor Codey announced the bill as the strongest legislation against pay-to-play in the US.

Management

The members of Citizen Campaign who drafted the pay-to-play bill were highly educated experts: Derek Bok was a former Harvard University president, Gary Stein a former New Jersey Supreme Court judge, and Craig Holman, who consulted on the project, was involved in the drafting of proposed reforms at the New York University School of Law.

The executive orders were passed by successive governors who were able to manage the legislation successfully through the state machinery.

Measurement

The impact of the legislation was measurable in terms of the decline in the contributions to political parties made by prospective contractors. In 2005, The Star-Ledger reported that the 10 contractors that had been the biggest campaign contributors had halved their electoral donations.

It is more difficult to assess in terms of the money saved by the state of New Jersey in its procurement process and the increases in value for money and quality of the infrastructure work carried out by contractors.

Alignment

As stated above, neither the democrats nor the Republicans was enthusiastic about the bill, which would close off a lucrative source of funding. Only two days after implementation of the law, it was reported that the Democratic party, with the help of lawyer Angelo Genova, had found a way around the bill. Genova was one of a handful of people to be consulted by McGreevey in drafting the original executive order. This shows that despite their support, they were not aligned towards the common interest, i.e., ending pay-to-play donations.

After the statutory loophole which banned county and local governments from enacting their own pay-to-play law was closed by Governor Codey, local authorities started adopting the legislation in significant numbers. This shows that the local bodies were sufficiently motivated to adopt the law once they could do so.

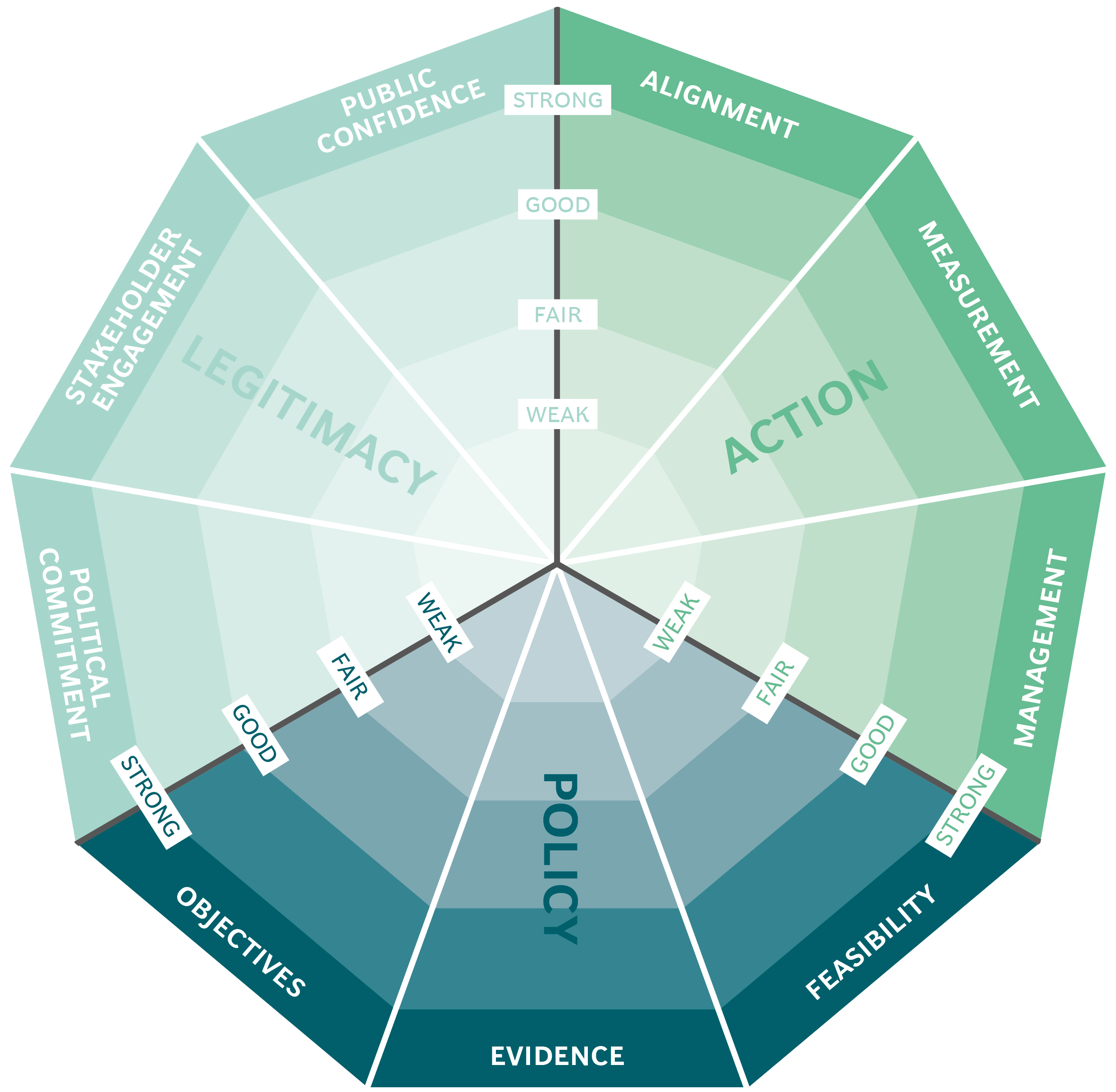

The Public Impact Fundamentals - A framework for successful policy

This case study has been assessed using the Public Impact Fundamentals, a simple framework and practical tool to help you assess your public policies and ensure the three fundamentals - Legitimacy, Policy and Action are embedded in them.

Learn more about the Fundamentals and how you can use them to access your own policies and initiatives.

You may also be interested in...

BANSEFI: promoting financial inclusion throughout Mexico

Formalising the appointment and compensation of Chile’s senior civil servants

Rainfall insurance in India

Microcredit in the Philippines