Banking Reform in Indonesia

The initiative

On 31 October 1997, the first agreement with the IMF for restructuring the banking sector was approved by the Government of Indonesia. The arrangement looked to stabilise the rupiah, limit the economic downturn, contain the surge of inflation back to a target of 5 percent, and reduce the external current account deficit to below 3 percent of GDP.[3]

The timeline of implementation of the restructuring included the following events:

- 31 October 1997 - Agreement on first IMF-supported programme with Indonesia

- 1 November 1997 - Bank resolution package announced; 16 commercial banks closed; limited deposit insurance for bank depositors

- 27 January 1998 - Indonesian Bank Restructuring Agency (IBRA) set up (by the IMF and the Indonesian government) and a blanket guarantee announced. IBRA was established to act on behalf of the government as the main entity leading the restructuring. Its role was initially to take over non-performing loans of the state banks, and later to act as shareholder in the formerly private banks

- 23 February 1998 - First chairman of IBRA dismissed

- 11 March 1998 - President Suharto re-elected

- 4 May 1998 Approval of revised IMF-supported programme

- 21 May 1998 - President Suharto replaced by B.J. Habibie

- 29 May 1998 - Bank Central Asia (largest private bank) taken over by IBRA.[4]

After two years of fragile and partial accomplishments, the newly-elected government of B.J. Habibie negotiated a new three-year extended arrangement of about USD5 billion with the IMF, which was approved by the IMF's executive board in February 2000. Then in January 2003, Indonesia's government, allegedly under pressure from legislators, declared that it wanted to break free of its commitments to the IMF.[5]

The challenge

There were three main factors that contributed to the vulnerability of Indonesia's banking sector during the crisis in 1997:

- Comprehensive reforms that took place in 1988 had led to a rapid expansion of the banking sector without strong prudential regulations or central bank supervision. As a response to declining oil prices in the early 1980s, Indonesia deregulated its financial sector to direct domestic savings into developing new industries. Reforms included a removal of credit ceilings, a reduction in the number of credit categories financed by liquidity credit, the removal of controls on state banks' deposit and lending rates, and the termination of their deposit rates.

- There was a high concentration of ownership in the sector, which led to weak corporate governance of the country's banks. Despite the regulations and requirements that were introduced, governance in the banking sector was weak, and there was little incentive for banks to be cautious in their corporate lending.

- The economic boom and increased international financial integration in the 1980s increased the structural vulnerability of Indonesia's financial system. Indonesia's reforms since the 1980s had aimed to move the economy away from a dependence on oil export towards higher-growth sectors. As a result, capital surged into the country with a progressive integration with global financial markets. This, however, exacerbated domestic macroeconomic cycles, and let to an overheating of the economy in the early 1990s.[1]

An exchange rate and interest rate shock in July 1997 triggered the crisis, and had a dramatic effect on the balance sheets of banks and highly leveraged corporations. “As a result of the exchange rate collapse, banks had to repay in full their liabilities in foreign currency when loans extended in foreign currency were not fully repaid. The liabilities of banks increased sharply owing to their exposure to interest rates, while corporate distress affected the value of bank assets. In the following months, a combination of a crisis of confidence, which was related to initial policy miscalculations, further rounds of exchange rate and interest rate rises, hyperinflation (inflation reached close to 80 percent in 1998) and the contraction of the real economy (-14 percent GDP contraction in 1998), worsened the distress in the banking and corporate sectors. A limited banking crisis quickly became a systemic banking crisis.”[2]

The public impact

In the years following the crisis of 1998-99, the Indonesian banking industry made significant progress, as evidenced by a stabilisation of the country's GDP growth and inflation, as well as banking indicators:

- By 2005, market risks remained high - even though the exchange rate fluctuations levelled off, the Bank Indonesia (BI) Rate was predicted to remain high up to the third quarter of 2006 as the Central Bank tried to bring down inflation expectations to a medium-term path of around 8 percent by the end of 2006.[6]

- Annual GDP growth almost went back to 1997 levels by 2002 - after a significant fall during the crisis - and inflation stabilised to 5.9 percent. However, investment inflows to the country remained very low in 2002 (0.07 percent of GDP) and returned to being negative in 2003.[7]

- “The ratio of lending to total assets also declined significantly. While claims on the central government, or government bonds injected by the government into the banking sector, increased to around 40 percent of total assets. As a result of a public capital injection (recapitalisation) worth IDR658 trillion (52 percent of GDP in 2000), the ratio of capital to total assets turned positive by 2000.

- “The nonperforming loan ratio declined to a normal level by 2002. The banking sector climbed out of its critical state thanks to the emergency treatment, but the pace of the recovery of financial intermediation has been slow since 2002 in terms of lending activity, due in part to more stringent risk management by banks after the reform”.[8] In January 2003, the Indonesian government terminated its deal with the IMF ahead of schedule.

Stakeholder engagement

The main stakeholders included the government, BI, the IMF, IBRA and the Financial Sector Action Committee (FSAC). From the beginning of the crisis, the authorities attempted to ensure the necessary coordination of various interested government parties and other public sector agencies through a series of high-level committees. “In late 1997 such a committee was established reporting directly to the President. But it rarely met and was not effective.”[9]

The FSAC was formed at the time and included economics ministers and the governor of BI under Coordinating Minister Ginandjar. Although this committee also occasionally met in the early months of the administration, it was argued that it had become increasingly intrusive in respect of the operations of IBRA as time went on.[10]

With regard to the IMF's role, their participation in the design of the policy was questioned, and they were accused of intervening in Indonesia without proper knowledge of the situation. “The IMF sent in a team of people unfamiliar with Indonesia and expected them to design a comprehensive economic restructuring programme in about two weeks.”[11]

Political commitment

The government demonstrated a commitment to restructuring the banking system at the outset of the crisis by signing its agreement with the IMF. As the negative effects of the tightening policies became apparent, however, the commitment was reduced in favour of political interests.

The restructuring of the banking system in Indonesia was closely tied to IBRA. The government appointed as chairman a highly regarded senior finance ministry official, Dr Bambang Subianto. The finance minister at the time declared that "the government recognised bank restructuring to be a government responsibility". However, although IBRA was intended to be an independent agency, its centrality to the restructuring process created an ongoing tension between its officials and the political interests that it appeared likely to threaten. As the extent of restructuring became apparent, these tensions increased. The first chairman was dismissed after a month, reportedly for being "too diligent in pursuing his responsibilities" and was replaced by a BI deputy governor.[12]

A weakened commitment was therefore apparent both from the existing Suharto government at the time of the crisis and from the IMF. “Suharto's unwillingness to enforce policies that might damage the business interests of his family and close associates, his inconsistency, and ultimately his confrontational approach undermined confidence and accelerated Indonesia's economic contraction. The IMF's lack of familiarity with the Indonesian economy and its key institutions, and its poorly conceived reform programme did the economy far more harm than good. Together, they took a bad situation and made it much worse than it should have been.”[13]

Public confidence

The suddenness with which banks were closed during the crisis sparked consumer panic and further exacerbated the crisis. “The manner in which the banks were closed sparked major consumer panic. Instead of announcing why they were being closed - and putting a deposit guarantee in place - Suharto simply shut 16 banks down in November 1997. People rushed to withdraw deposits from the banks in question and from other banks, while rich investors whipped cash overseas. BI estimated that ultimately some USD40 billion fled offshore, fearing a crackdown on corruption and a meltdown in the rupiah.”[14]

In addition, it sparked the uncertainty and loss of confidence over the capability of the institutions responsible for managing the situation. “The first crisis support agreement of the Indonesian government with the IMF exacerbated the public's loss of confidence in the banking system because, in the absence of clearly stated criteria for closures and of information on the soundness of the remaining banks, there was great uncertainty about which banks might be closed next. At the time, the government guaranteed deposits in the closed banks only up to an amount of IDR20 million - then equivalent to about USD6,000.”[15]

Clarity of objectives

The objectives stated by the Government of Indonesia at the outset of its agreement with the IMF were clear and measurable, although some targets were modified during implementation.

The Letter of Intent (LOI) submitted by the Government of Indonesia in October 1997 stated the following macroeconomic objectives for the three-year programme:

- “Stabilising the rupiah while maintaining gross foreign exchange reserves at a comfortable level;

- “Limiting the economic downturn during the remainder of this year and next year, before restoring economic growth to its potential rate before the end of the programme;

- “Containing the initial surge of inflation emanating from the depreciation and other one-time factors to no more than 10 percent through 1998/99 and bringing it gradually back to 5 percent subsequently;

- “Reducing the external current account deficit to below 3 percent of GDP, a level that should ensure a steady decline in the external debt and debt service ratios.”[16]

The first LOI also stated the strict intention to raise the minimum acceptable capital adequacy ratio to 9 percent by the end of 1997 and to 12 percent by the end of 2001. However, the October 1998 LOI already showed a change in this objective. “Despite the previously expressed intention to strengthen prudential standards for the banking system, the policymakers were so keen to minimise the number of further bank closures that they decided instead to soften the most fundamentally important of those standards: namely, the minimum acceptable capital adequacy ratio. The near-term target was now set at 4 percent, rather than 9 percent- the standard originally to be achieved by September 1997.”[17]

Strength of evidence

An article published in the Cato journal in 2002 indicated there were strong similarities between the Indonesian banking reforms and the mechanisms implemented in Sweden to manage their own banking crisis a few years earlier. “As the crisis deepened in mid-1998, the government and the IMF therefore drew up plans for recapitalising some of the insolvent banks and merging or closing down the rest. These plans appear to have been strongly influenced by those adopted by Sweden to resolve its own 1991–94 banking crisis.” [18] However, this was an external observation, and it is not clear what specific measures were taken from this experience, or whether they were properly adapted to the Indonesian context.Feasibility

The country held several consultations on how to manage the banking situation, and had the support of the IMF. Despite this, some of the specifics of the restructuring were not adequately assessed, and several mistakes were only identified over time.

After Indonesia's first LOI cited the need for "institutional, legal, and regulatory" reforms, the IMF and BI noted that “the prudential regulations introduced before the crisis not only contained loopholes, but that there were also problems with the very legal framework that made these regulations effective”.[19]

It was only after the initiative was implemented that it was realised that the amount of government bonds needed to recapitalise the banks was significantly higher than initially envisaged. “As a percentage of GDP, the amount of government bonds needed to recapitalise the banks is more than four times the proportion initially estimated, and the net fiscal cost of bailing out the banks will probably be about a third of annual GDP - and about four times larger than the total amount that had been lent to Indonesia by the IMF by mid-2001.”[20]

The legal system in the country was unsuited to managing the complexities of such a challenge. “The legal system itself was chronically weak. Judges were often poorly educated, corrupt, and ill-informed about complex financial loan arrangements. This was to prove a major stumbling block to Indonesia's recovery, as foreign banks would find it near impossible to recover debt from delinquent debtors via the bankruptcy courts.”[21]

Management

IBRA was given the responsibility of taking over the most severely non-performing loans from all the recapitalised banks (both state and private) and of taking control of a huge portfolio of private sector assets. These were handed over to secure the interest the government had acquired in the private banks.[22]

However, IBRA -which was meant to be independent - was strongly influenced by political interests from the start. “As the government aimed to minimise its losses, it responded with a continuing series of changes to the leadership of IBRA, to the control of IBRA by the government, and to IBRA's strategies for asset recovery, as well as to repeated protestations as to the government's serious intention to take strong legal action against recalcitrant bank owners if they were not more cooperative in cutting down the government's own losses. All to no avail.”[23]

The IMF provided essential support and guidelines for the implementation, but was criticised for managing the situation badly, and even of sending a team of people unfamiliar with the country to design the economic restructuring programme.[24] The International NGO Forum on Indonesian Development (INFID) also criticised the World Bank and the IMF for “failing to properly supervise the use of loan funds which were intended to help refinance the shattered banking sector. The criticism has been prompted by allegations of corruption involving IBRA (set up and financed by the IMF), Bank Bali, and the ruling Golkar party.”[25]

Measurement

The government defined a set of five quarterly quantitative performance criteria to monitor the progress under the programme:

- "A ceiling on base money;

- "A floor on the net international reserves of BI;

- "A floor on the overall government surplus;

- "A ceiling on the contracting of external public and publicly-guaranteed loans with maturity of more than one year;

- "A ceiling on the stock of public and publicly guaranteed short-term external debt.”[26]

From December 1997, authorities planned to publish biweekly data on key elements of BI's foreign exchange position. “To improve transparency, and allow market participants to make more informed assessments of economic developments, the publication and dissemination of key economic data will be improved substantially. From December 1, 1997, the authorities will publish biweekly data on key elements of BI's foreign exchange position, including gross international reserves and external liabilities.”[27]

They also planned to publish data on Indonesia's financial institutions. “The authorities are also working closely with other regulatory agencies and with financial institutions to ensure they publish regular and comprehensive data on the financial condition of the latter, including on nonperforming loans, capital adequacy, as well as ownership structures and affiliations. Monthly data on all central government activity (including domestic revenues and expenditures) will be collected and released within two months of the end of each reporting period. To improve further the provision of high-quality data to the public, additional technical assistance from the IMF has been requested, so that Indonesia's data can be brought into compliance with the Special Data Dissemination Standard, by December 1998.”[28]

Alignment

There was partial alignment between the Indonesian government and the IMF, as well as among local institutions responsible for making the restructuring work. But they also faced several disagreements in the process that led to the termination of the partnership once some of the objectives had been achieved.

A lack of coordination and solid commitment to the restructuring by all parties contributed to the ineffectiveness of the initiative. Some of the main factors that contributed to this and to its high costs were:

- “Long delays in resolving the banking crisis, in particular the bank closures and recapitalisation programme;

- A lack of understanding of the causes and the extent of the crisis, which led to the adoption of inappropriate strategies (e.g. a piecemeal approach to banking closures);

- "A lack of coordination and consensus between the authorities in managing the crisis;

- "A lack of commitment to take 'hard' measures to solve the crisis, e.g. to close all insolvent and non-viable banks at the outset of the crisis and to avoid political intervention;

- "A lack of law enforcement and legal and regulatory weaknesses, which fostered moral hazard.”[28]

Following his re-election, Suharto named a new cabinet, removing many of his economic managers and filling it instead with close associates, including his daughter. “The composition of the cabinet was interpreted both domestically and by foreign observers as a sign that Suharto was much less interested in economic reform than in consolidating the power of his family and close associates. Domestic opposition became more vocal, and student protests began to flare up.”[29]

Over time, there were increased disagreements between the government's objectives and the priorities of the IMF. This made their collaboration difficult and hurt the public's perception, eventually leading to the end of the partnership. “The heated and very public arguments for tighter policies and effective conditionality unnerved financial markets. The interaction between the IMF and the Indonesian government quickly degenerated to the stage where the market perceived the programme to be under threat, and this was fatal for market confidence.”[30]

Bibliography

IMF and Bank failed to spot Indonesia corruption, 15 September 1999, Bretton Woods Project

Indonesia's Battle of Will with the IMF, Smitha Francis, 25 February 2003, Global Policy Forum

Indonesian Banking Crisis, Gráinne McCarthy, Initiative for Policy Dialogue

Letter of Intent of the government of Indonesia, 31 October 1997, International Monetary Fund

The IMF and the Indonesian Crisis, Stephen Grenville, 2004, International Monetary Fund

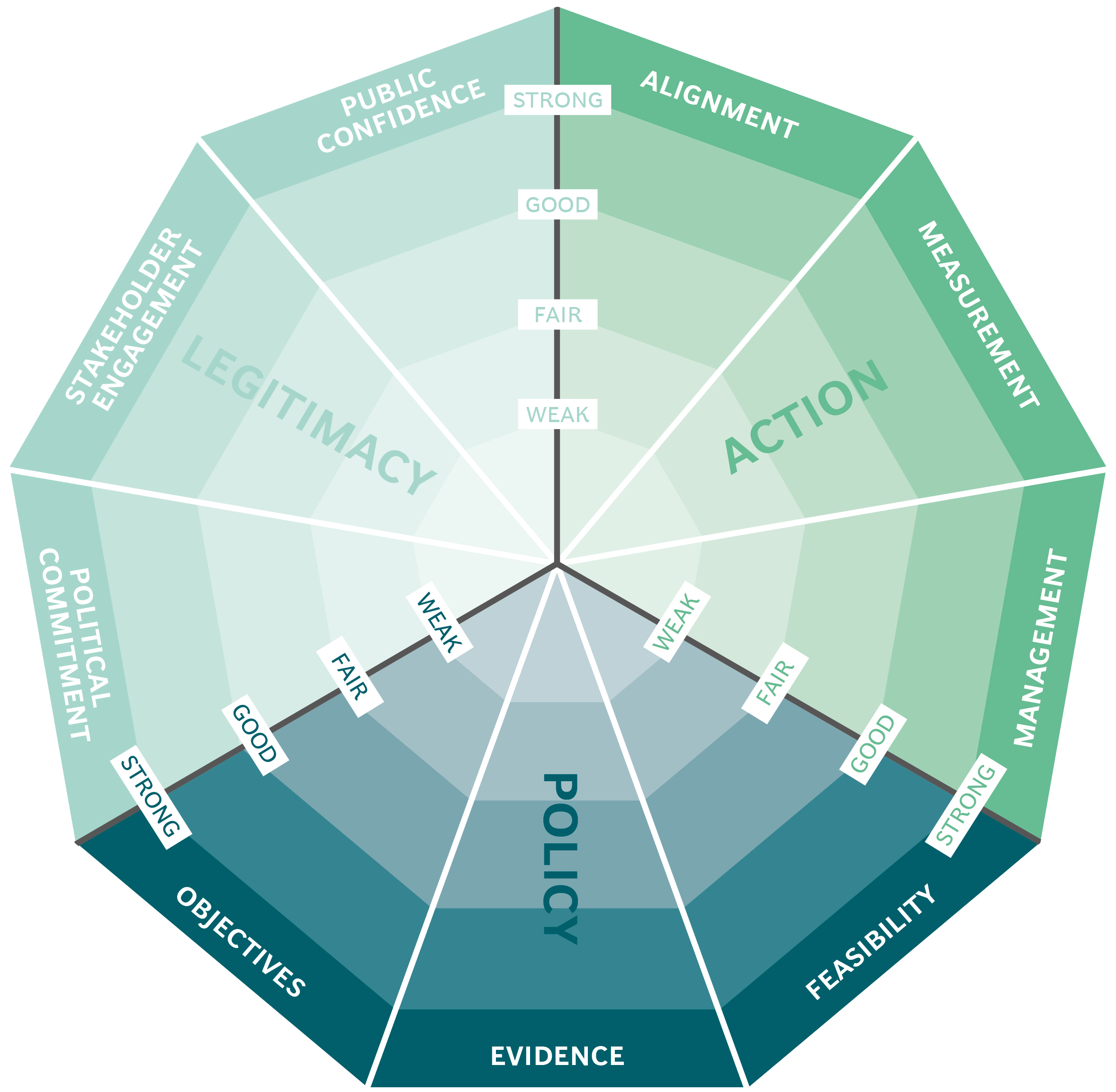

The Public Impact Fundamentals - A framework for successful policy

This case study has been assessed using the Public Impact Fundamentals, a simple framework and practical tool to help you assess your public policies and ensure the three fundamentals - Legitimacy, Policy and Action are embedded in them.

Learn more about the Fundamentals and how you can use them to access your own policies and initiatives.

You may also be interested in...

ChileAtiende – a multi-channel one-stop shop for public services

Mexico City's ProAire programme

National portal for government services and Information: gob.mx

BANSEFI: promoting financial inclusion throughout Mexico